The Untapped Political Potential of Canadian Youth

The Parliament Building in Ottawa, Ontario. "The Parliament of Canada" by Michel_Rathwell is licensed under CC BY 2.0

The Parliament Building in Ottawa, Ontario. "The Parliament of Canada" by Michel_Rathwell is licensed under CC BY 2.0

In the 2019 Canadian Federal Election, young people constituted the largest voting bloc, outnumbering the ‘Baby Boomers’ for the first time. Those between the ages of 18 and 38, or ‘Millennials’, made up about 37% of the total Canadian electorate, giving them unprecedented power in deciding the outcome of the election. Young people had the power to bring issues that matter to them, like climate change, to the forefront of the campaign, and broadcast the voices of youth in Canadian politics.

By looking at voting statistics alone, it is clear that young people hold a lot of political sway. They represent a large chunk of the electorate and, while general Canadian voter turnout is decreasing, youth voter turnout rates are increasing; more youth, especially university students, voted in 2019 than in previous years. Young people are now also more likely than older generations to be politically-engaged, through public demonstrations and signing petitions. If a candidate is able to mobilize young people to support their cause and inspire them to not only vote for them but actively campaign for their cause, the candidate will be more likely to succeed.

This was the case in 2015, when a surge in youth turnout contributed to the Liberals winning a majority. Since then, political discussion has continued shifting towards topics that are important to youth. For example, climate related issues, like carbon pricing and pipelines, were main topics of discussion in the 2019 elections. Additionally, all major parties had plans to increase the number of jobs and vocational training available, ease the way for first-time homeowners to purchase real estate, make university cheaper, and reduce the cost of living, all of which are issues that are particularly important for younger demographics. Furthermore, candidates also appeared to campaign in ways that would appeal to young voters. Much of the campaign was brought to social media, where candidates heavily promoted their platforms and attacked political rivals. The online push worked: Jagmeet Singh, for example, saw his poll numbers increase after engaging with youth-dominated social media platforms like Tik Tok and Twitter. However, some young people see the progression to include youth in politics as too slow, and, as such, have decided to run for office themselves.

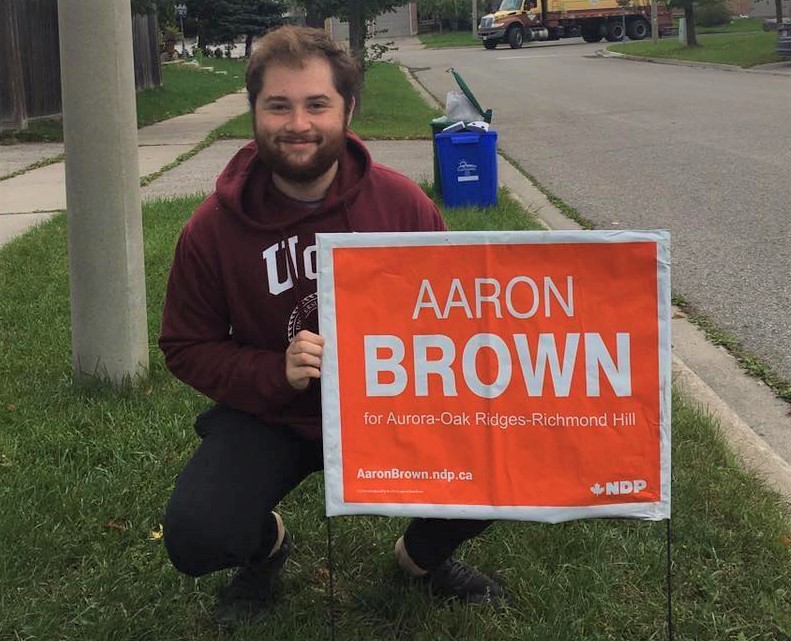

“I was tired of not being heard, of not being represented,” said Aaron Brown in an interview with MIR. He ran for Member of Parliament for the NDP in the riding of Aurora – Oak Ridges – Richmond Hill in Ontario. At the time of his electoral campaign, Brown was 20 years old and studying International Development and Political Science at the University of Toronto. Brown ran on a platform of health care reform, climate action, tackling the housing crisis, and personalizing politics to make it about everyday Canadians. While Brown’s platform represents the typical NDP platform, Brown is definitely an atypical politician. In fact, he believes he is not a politician at all.

“I tell people that [I’m not a politician], because I think ‘politician’ has a bad reputation,” said Brown. “I’m not here to play games. I’m here to make life better for people in my community.”

This personalized approach to politics is characteristic of young candidates, such as Kira Brunner, a 19-year old McGill student who ran for MP in the riding of Elk Point, Alberta for the Green Party.

“Giving all Canadians the opportunity to feel represented in their government [motivates me],” said Brunner. “Everyone should have the opportunity to make their vote matter.”

Brunner and Brown are actively challenging the classical definition of a politician. Neither expected to win in their respective ridings, but rather, they sought to highlight the issues they were passionate about in their districts. They are further challenging the narrative of apathetic youth and redefining the role of young people in politics.

“I would like to change the thinking around [youth participation in politics.] Telling young people how I ran and how they can get involved in their community,” said Brunner. “Youth are getting less and less likely to regurgitate the ideas of the parents. We can think for ourselves.”

Brown also expressed hope in the power of social media as a conduit for the youth voice and as a means to revamp Canadian electoral politics.

“We have to look at our overall system,” said Brown. “Young people have to go to school, look after their families, have a part-time job. It’s a lot easier for old, retired people to participate in politics, but there are ways to make it easier [for youth] to get involved, and I think social media is one of those ways.”

Challenging the system appears to be a consistent theme among young candidates. Both Brunner and Brown advocate for the implementation of proportional representation, but also for a shift from party and power politics to adequate representation of local communities. The need for local representation in Ottawa is undoubtedly a current subject of debate in Canadian politics, specifically in Brown’s riding, from which MP Leona Alleslev hails. In 2018, Alleslev made headlines by crossing the floor from the Liberal party to the Conservatives, prompting polarized responses from people across the political spectrum.

“I found it disrespectful to all the people in my riding,” said Brown. “There’s no situation where you can just cross the floor without consulting the people in your riding.” Alleslev’s actions demonstrated the disconnect between federal MPs and the communities they are supposed to represent. In neglecting to hold a by-election or adequately consult her constituents, some feel Alleslev betrayed those who voted for her on a Liberal platform.

Brown and Brunner both prioritize representing their constituents in their politics, rather than any personal interest or claims of being the ‘best person for the job.’ Their pitch: that they care about their communities and want to go to Ottawa to represent their electorates. However, for them, being a MP is not just a job or the first step to becoming Prime Minister. In fact, it’s personal.

“When I’m talking about things like climate change, I’m not talking about my kids or my grandkids,” said Brown. “I’m talking about me!”

This personalization of politics may claim more ground as younger generations inherit more political power. In challenging the definition of a politician and advocating for electoral reform that is more proportional and representative of the interests of voters, youth candidates are shifting the political landscape to make it more accessible to and representative of young people. Furthermore, by tapping into the political power of young people, parties may benefit from a motivated, engaged, and growing voting bloc. In a time of significant division along party lines, a shift to focusing on the interests of individuals and communities may serve to reinvigorate Canadian politics. Young people are increasingly gaining power in politics; it is about time they get representation, too.

Featured image: The Parliament Building in Ottawa, Ontario. “The Parliament of Canada” by Michel_Rathwell is licensed under CC BY 2.0

Edited by Rebecka Eriksdotter Pieder