The War on Carbon: Climate Security as National Security

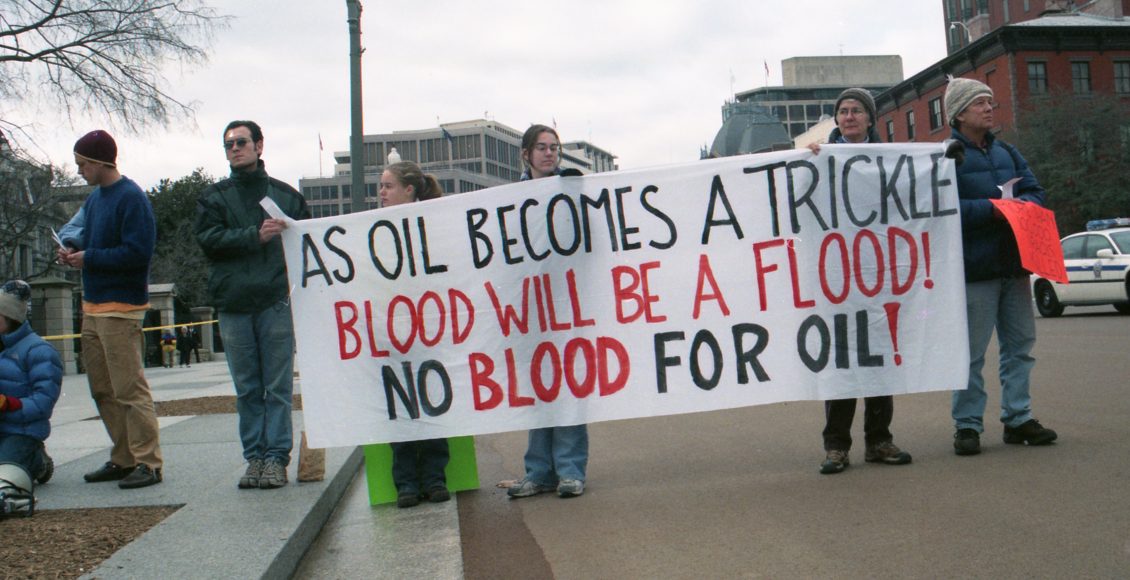

Protestors warn of natural resource conflict https://bit.ly/35A3GiZ

Protestors warn of natural resource conflict https://bit.ly/35A3GiZ

When people talk about climate change, they don’t generally think about war. Climate change used to be about having hotter days, switching light bulbs, and recycling more. Today, however, it has become a matter of life or death.

This urgency extends beyond dynamic weather, such as flooding, tropical cyclones, and drought. The talk is shifting towards how it will directly impact certain countries’ abilities to defend themselves, and even asking if it will eventually be a cause for conflict.

Former U.S. Vice President Joe Biden’s said at CNN’s marathon Climate Town Hall that “Climate change is the single greatest concern for war and disruption in the world, short of a nuclear exchange.” His words are a dire warning, and it is certainly a change in tone among the political frontrunners. Mayor Pete Buttigieg and current Democratic election candidate called it “The security challenge of our time”, and the Pentagon released a report outlining the increasing vulnerabilities of military installations due to climate change. This all occurring underneath a White House that continues to deny climate change and actively downplays its effects to the public.

Rather than being some distant menace to humanity’s survival on earth, the dangers of climate change are becoming increasingly quantifiable. The Pentagon’s report outlines how flooding, drought, desertification, wildfires, and permafrost thaw each pose a risk to the future of domestic and international U.S. bases. These vulnerabilities not only inhibit the United States’ daily operational capabilities, but they will also make many of these bases uninhabitable.

While there are direct threats to U.S. national security, climate change poses indirect risks as well. Such an idea is not new. An article from as far back as 2003 outlines the potential threats of accelerated climate change. While previous wars were fought over ideology and land, future military confrontation “may be triggered by a desperate need for natural resources such as energy, food, and water”.

Climate change can and will alter the availability and distribution of life’s most basic needs, and it will be added to the already extensive list of reasons for war. However, it also acts as a modifier for existing conflicts. Refugee flows due to climate change help to create the “perfect storm” that “feeds a spiral of violence” in already vulnerable areas.

Biden acknowledged such fears in the climate town hall as well, asking the issue, “what happens if you get 10, 12, 13, 15, 100 million people on the move? It causes wars!”.

However, is this the best way to look at the environmental crisis? Are thoughts of war and conflict needed to change how we perceive and act on climate change, or will they simply lead to unproductive panic? We can look back at the ‘War on Drugs’ as an example.

Beginning in the 1980s, the Pentagon and the Reagan White House expanded the view of the narcotics trade as a national security issue, threatening democratic institutions, growing violence, and destabilizing democratic allies. Such a point of view led to quick and decisive action against drugs, involving the U.S. defense apparatus in the process.

The military was tasked with “sealing the borders” and was heavily pressured by various branches of government and the public to directly impede production in the source countries (an action the joint chiefs of staff were reluctant to take). Budget funding for fighting drugs was placed alongside Iraq and Afghanistan in the Bush administration’s list of priorities. Military equipment and funding also went overseas to help Latin American countries fight a war that continues up to today.

The hysteria surrounding the war on drugs led to 800% increase in drug-related incarcerations between 1980 and 1997, and in Mexico alone, the drug war has killed more than 200,000 people since 2006. By framing the issue of the drug epidemic in the U.S. as an immediate, urgent national security issue, it led to an immediate, urgent response from government agencies. National security is prioritised heavily above all else by heads of government, and its maintenance will come at almost any cost.

With that in mind, today’s situation does have its differences. For one, there seems to be a continued disconnect between the White House and government agencies in the realm of the environment.

While the Pentagon has released their report, some lawmakers have said that the report has left out details requested by Congress, such as listing the most vulnerable bases and ideas to combat the threat. The report was almost an acknowledgement of a potential threat while admitting as little as possible to promote inaction.

Meanwhile, top administration officials reassure the public that there are no risks while their own agencies conduct research that says otherwise In fact, there is evidence that administration officials actively seek to downplay or even limit research on the dangers of the changing environment.

Both of these situations demonstrate that the executive branch is willing to subvert its own climate-conscious agencies in order to promote its policy of climate denialism. Such a disconnect slows down the roll out of policies responding to the research. While that delays an eventual solution to the climate emergency, it does help to prevent any collateral damage.

As was seen in the war on drugs, good intentions do not necessarily make good policy. An immediate and urgent response can cause more damage to already vulnerable communities for the sake of national security. Governments’ desire to strengthen climate security should be a streamlined, direct approach that does less harm than good, focusing on the source and accounting for the costs. The delay provides these agencies more time to process the security risks of the environment and develop suitable plans for an administration willing to listen to them.

Government is capable of quick and decisive actions, but unfortunately for the climate movement in the U.S., action may only come when conflict is on the table. While agencies are being held back in expanding on and responding to the threats, the trend seems to be heading in that direction, with the tone in the U.S. and elsewhere signalling greater awareness of the risks. While today’s administration continues its policy of denial until proven otherwise, future governments will need to delve deeper into the threats of climate change to their security, and consider every option on the table if they are to face this absolute, existential threat.

Edited by Elizabeth Hurley