There Are No More Second Chances

https://www.flickr.com/photos/howlcollective/12568946385

https://www.flickr.com/photos/howlcollective/12568946385

On October 21, the Canadian people will vote in the federal elections to decide on who will represent them in parliament for the next four years. The campaign trail has been full of promises of economic growth, affordable housing, “innovative” climate change combatants, and comprehensive healthcare reform, with each of the different party leaders claiming monopolies on each policy. While reforms in each of these sectors are important, these topics have dominated nearly all political discourse, leaving little room for any conversation on one of Canada’s most marginalized groups: the indigenous populations.

Many of the key figures in the upcoming elections have spoken out about ‘indigenous issues,’ but few have provided any concrete plans on how they plan to help the First Nations, Inuit, and Métis communities as they continue to struggle with poor infrastructure, inadequate healthcare, systemic violence against women, and high suicide rates. In fact, during the first, and only, English-speaking leaders debate held on October 7, when asked to discuss indigenous issues, the majority of the conversation tended towards character-bashing and the insufficiency of current climate-related policies; there was hardly any mention of indigenous people nor the epidemical violence they are facing. With rhetoric continuously taking precedence over substance, it is unsurprising that there are no clear paths forward for empowering indigenous communities coming into the 43rd federal election.

The 2019 Elections

Prime Minister Justin Trudeau has repeatedly stated that there is no relationship more important to him than that between the federal government and Canada’s indigenous communities. However, many of his policy decisions over the last four years seem to directly contradict this statement. In fact, when Trudeau called the 2019 election, he made no mention of indigenous people, further normalizing the silence surrounding indigenous issues in federal politics. Andrew Scheer, the leader of the Conservative Party, has been lukewarm on indigenous issues, mainly proposing sweeping “promises of change”, that bare little weight in actual policy-making. Scheer has regularly cited the number of First Nations reserves in his constituency as a testament to how much he knows and cares about indigenous peoples and yet, he has been repeatedly distant from the communities in his own riding. He failed to attend the annual Federation of Sovereign Indigenous Nations (FSIN) meeting last May despite the fact that it was only 300km from Saskatoon, not far from Scheer’s riding in Regina. It is problematic and dangerous that the leaders of Canada’s two, biggest political parties seem to care so little about one of the country’s most persecuted groups.

While polls are signaling that the election will likely come to head between the Liberals and the Conservatives, there are several other parties also vying for seats in 2019. Jagmeet Singh, the leader of the New Democratic Party (NDP), has addressed indigenous issues more directly in his platform, notably pointing to systemic problems in educational opportunities, a lack of clean drinking water, and gaping holes in the Liberal’s current indigenous-related policies. Elizabeth May, the leader of the Green Party, has incorporated indigenous issues into her platform and has taken a robust stance on promoting human rights across indigenous communities. Although the NDP and the Green party have put forward more specific policies on indigenous issues, the likelihood of either party forming a government is so slim that, sadly, many of their promises will, likely, never be realized.

Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada (CIRNAC)

Unfortunately, the overwhelming silence and lack of substantive policy isn’t unique to the 2019 elections: indigenous issues have never been a “hot topic” for Canadian politicians. If one were to look at the inexplicable hardships faced by indigenous populations around the country every single day, it would be impossible to find moral justification for why these communities are systematically overlooked and ignored at all levels of government. Over the last four years, Trudeau has made a number of claims to support indigenous empowerment, yet evidence of sufficient action is lacking. The Prime Minister often cites the inception of the inaugural Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada (CIRNAC) department as evidence of his care and concern for indigenous populations, and while the office has made some headway, significantly more still needs to be done.

Carolyn Bennett, the first and current Minister of CIRNAC, has echoed the Prime Minister’s wishes and calls for action, and she has worked tirelessly within her position to enact change. The Minister, through CIRNAC, has fought to increase the representation of First Nations, Inuit, and Métis people in policy-making and ensure that their voices are not only heard but prioritized in both the development and implementation of new programs and initiatives. Bennett has emphasized that listening to those who live through these hardships every single day has created an environment wherein pragmatism can meet efficiency and the mainstay “paternalism and the top-down, father-knows-best approach” of the past can be eradicated once and for all. Also emphasized in Bennett’s mandate is a focus on youth engagement and a call to not only include but champion the voice’s of young indigenous people in government decisions. In fact, Bennett has stated that “the most exciting part of [her] job is to meet with young leaders” because it is their future that is inevitably being fought for and shaped.

Colonial Impacts

When discussing indigenous peoples and the varied crises unfolding before them, one must recognize, as Bennett does, the circumstances and decisions that led to this systemic disenfranchisement. Colonialism is often discussed in relation to development and countries who fought for independence against European powers. Many Canadians forget that colonialism – dubbed “settler colonialism” – stampeded through North America as well, except here, there was no official fight for independence; there were conflicts and disagreements, and a number of treaties aimed at according indigenous peoples some semblance of rights, but much of the oppression and violence is as real today as it was one hundred years ago.

Bennett is careful to recognize this unfortunate reality when she discusses indigenous issues and adopts a pragmatism that many politicians, eager for quick-fixes, lack: most of those who are privileged to wear the title of ‘Canadian’ today are settlers and immigrants with a duty to create a future that upholds the very values that are continuously claimed as inherent to our national identity. On this note, Bennett emphasizes a need for a proactive approach rather than solely a reactionary one. The federal government is playing a desperate game of catch-up to rectify the serious, and at times irreversible, consequences of colonialism and failing to match these efforts with preventative measures for future generations. Bennett recognizes this disconnect, and while she understands that eliminating the lingering impacts of colonialism is imperative, policy must also focus on facilitating future autonomy and prosperity.

The Environment

While Bennett seems to evoke a genuine concern for indigenous populations and is intent on facilitating a network that will pave the way for future prosperity, specifically with regards to the environment, other members of the Liberal party, including the Prime Minister, seem to have ignored many of the environmental promises they made back in 2015. As of September 2019, Mr. Trudeau has confirmed two pipelines and an LNG plant that, in addition to causing a slew of environmental damages, will also disrupt several First Nations communities. When asked how the government plans to protect the affected communities, Mr. Trudeau offered a stump-style response, citing his administration’s ongoing talks with the affected communities and their supposed interest in the project as a testament to their supposed involvement in and endorsement of the projects.

Similarly, when asked about the role of indigenous communities in these industrial projects, Bennett has stated that she has had many “serious conversations on resource sharing” with relevant stakeholders who have expressed a personal, and financial, interest in the pipeline projects. While it is probable that there are select members from these indigenous communities who are invested in the pipeline projects, the general response offered by the federal government seems to rely on oversimplified accounts from a minority of individuals rather than a true consensus among all members. The more representative narrative seems to be highly critical of the environmental damages that will arise from the pipeline.

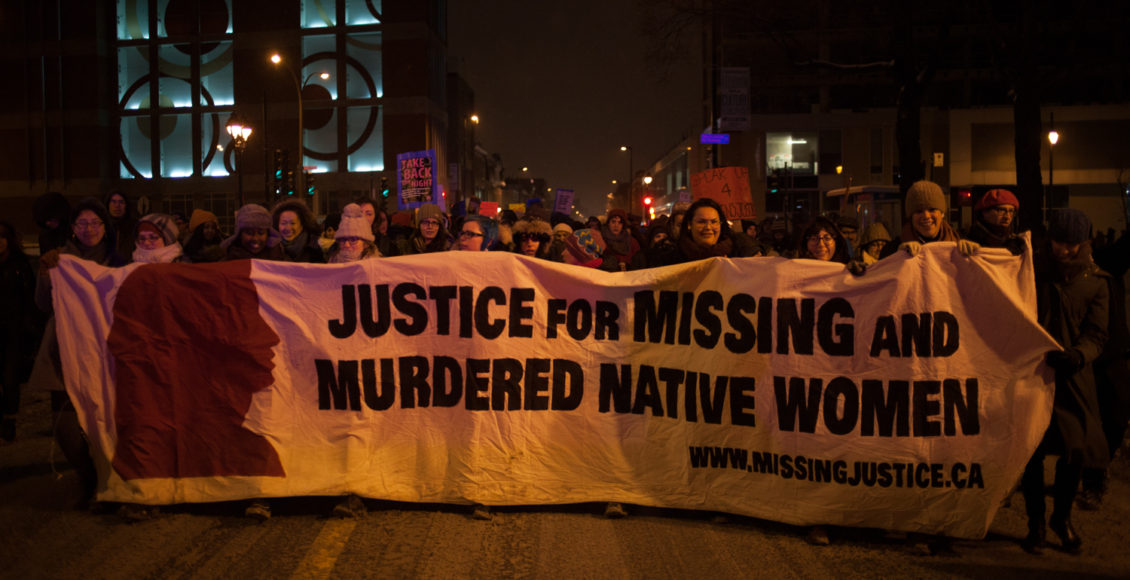

Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women

Another issue on which the Liberal government has fallen short, though this time with more immediate and unforgivable consequences, is the genocide of indigenous women. For centuries, Canada’s indigenous women have been systemically kidnapped, abused, and murdered, yet despite the numerous pleas on behalf of the affected communities, the federal government has largely ignored the atrocities. Shortly after he was elected, Trudeau became the first prime minister to launch a formal inquiry into the “Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women”, which was completed in June 2019, nearly four years after it was initiated.

The inquiry concluded with 231 calls to justice, an exorbitantly, though unsurprisingly, high number considering the scope of the inquiry and how many stakeholders are involved. The Liberal government has promised to create a National Action Plan to address the calls and hold accountable those responsible for its implementation. The Plan would include substantial reforms to education, housing, healthcare, and safety across indigenous communities, specifically in areas, such as the ‘Highway of Tears‘ in British Columbia: a stretch of road wherein numerous indigenous women have been taken. In terms of a timeline, Bennett has stated that “the [federal government] had hoped to have the [National Action Plan] in place by next June – a year after the inquiry report was tabled” to address these injustices, yet, given the decentralized nature of its roll out and the upcoming elections, it is unlikely that tangible change will be realized anytime soon.

What now?

While the Liberal government has made strides towards ending the persecution of and violence towards indigenous populations, the progress appears to have been largely symbolic. Many of the policy decisions that have been made over the last four years, specifically those related to the environment and indigenous women, have either born damaging consequences or have failed to adequately rectify the situation. Although reforms to an outdated system rooted in historical disenfranchisement will take time to implement, it is critical that immediate steps be taken at all levels of both government as well as within civilian circles to put in place substantive and sustainable policies.

One particularly impactful way of spearheading this change is by electing indigenous candidates to office. As the federal elections near, an increasing number of indigenous individuals are coming forward to run for office to ensure that their needs are advocated for in Ottawa. The Assembly of First Nations has stated that the upcoming election have a record number of indigenous candidates with, as of the latest report, 62 candidates running. While all levels of government, especially the federal government, have an obligation to support and empower indigenous communities, it is high time that indigenous people be given the opportunity to represent themselves and their own needs in government. With luck, the upcoming elections and heightened action will allow for just that.

The feature image, “missing justice 14 feb. 2014” by Howl Arts Collective is licensed under CC BY 2.0.

The article contains excerpts from the following podcast with Minister Carolyn Bennett:

Edited by Helena Martin and Charles Lepage.