Thinking Critically About Social Value: The Visibility of Race and Class During the Pandemic

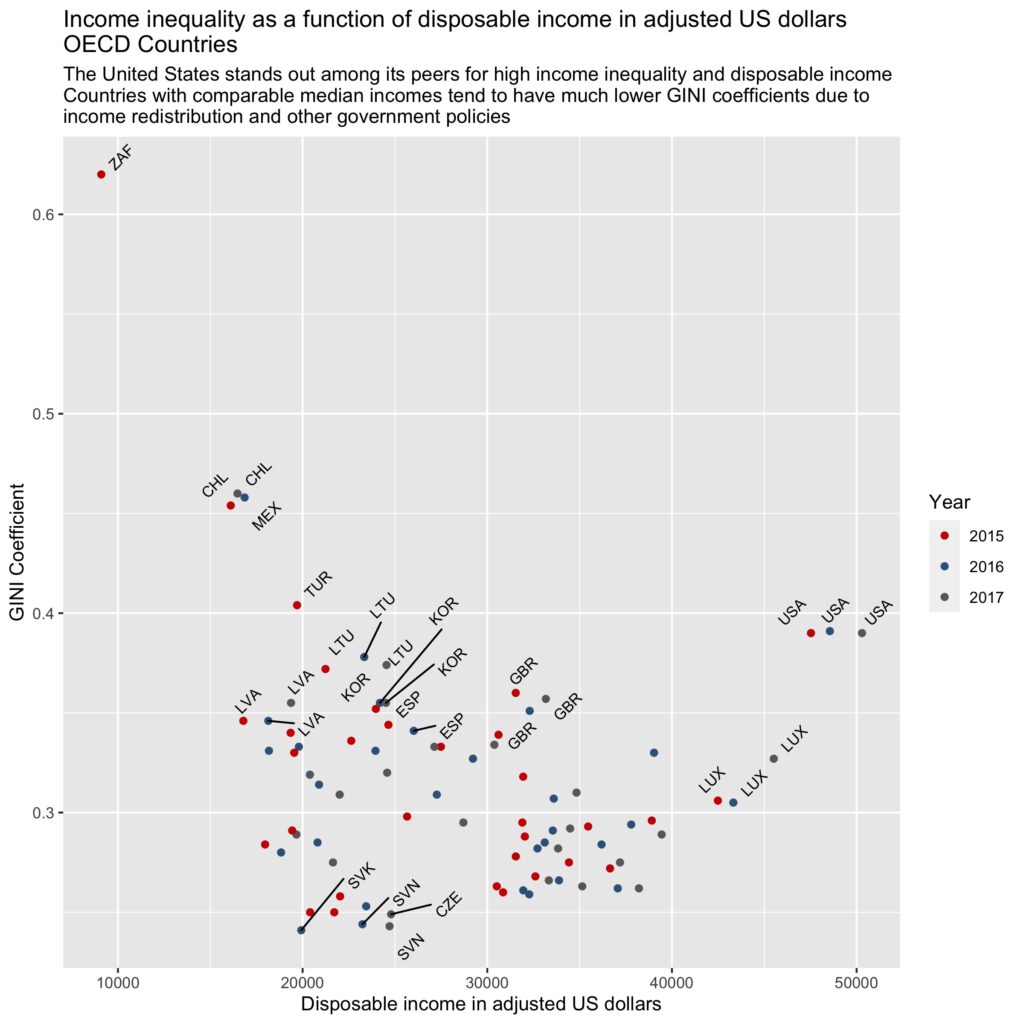

Growing income disparity and the power of the one per cent have sounded political alarm bells for the past two decades. However, COVID-19 is revealing these inequities, from disparity in health outcomes across races and ethnicities, to the ability of some to follow stay-at-home orders, to many citizens for the first time. In a society where some have amassed great fortune, how have others continued to be treated — at least in an economic sense – as worthless?

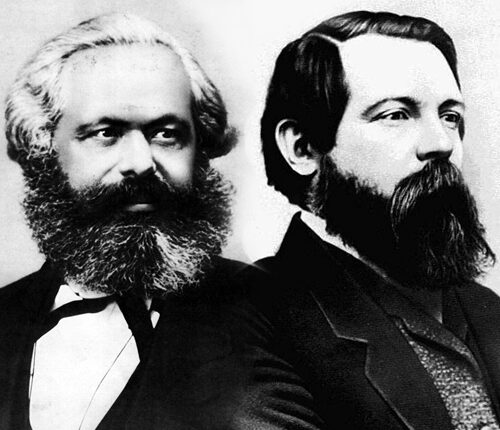

A century ago, the urban poor were viewed as inherently ‘inferior’ members of the human race. Today, such Victorian concepts seem antiquated. Somewhat surprisingly, other nineteenth century political theorists — Marx and Engels — put forward a different explanation for the development of a “surplus population” related to market forces, which remains relevant. The surplus population is considered to be the individuals who are unable to fully participate in society and are marginalized to live in what could be called subhuman conditions.

Critical theory and Marx: The disposability of the person

Narratives of surplus population in modern political thought typically trace back to Malthus’ concept of “redundant population.” Observing late eighteenth and early twentieth century Britain, Malthus believed that industrialization had created a surplus of resources that allowed the poor to procreate at a faster rate than in “nature.”[1] The idea may seem familiar as this concept purportedly inspired Darwin’s theory of evolution, which argues some are more ‘fit’ to thrive than others. By attributing a lack of success to people’s innate qualities, Malthus argued against government aid for the poor.

In contrast to Malthus, Marx and Engels explain the emergence of a socially undesirable class as a result of market forces rather than individuals’ inherent traits. They termed the individuals living in deep poverty the “relative surplus population” and the “industrial reserve army.” In their view of class, the size of an industrial reserve army varies relative to economic demand: during times of economic boom, these workers are employed, but during recessions, they become unemployed, casualties of a shrinking market.[2][3]

Members of the industrial reserve army do more precarious work and must survive in poorer living conditions. However, Marx and Engels did not view these conditions as reason for government intervention. Rather, they contended that this squalid life would spur the surplus army to morph into an actual force, forming the revolutionary body that would overthrow the bourgeoisie.[4] The two scholars’ critique of capitalism would give birth to a larger school of political thought known as critical theory, oriented around human liberation from oppression.

Low wage worker value: COVID-19 and disposability

During the COVID-19 pandemic, the term ‘essential worker’ is ubiquitous: on windows everywhere, people thank those who must go to work at a time when most all of us must stay home. ‘Essential’ conveys a sense of value rather than a sense of disposability, which is a status many frontline workers in the service industry experience outside of the pandemic. In fact, in response to the decision to roll back the $2 per hour raise for staff working in stores, the president of Unifor — the union that represents over 20,000 employees in retail across Canada – stated, “The pandemic did not make these workers essential and did not create the inequities in retail, it simply exposed them.”

The value of frontline workers was similarly called into question when Quebec Premier Legault announced that new hires in the province’s caregiving centers would earn more per hour than the current experienced personnel. As in grocery stores, the rise in wages is due to the risk of exposure to COVID-19 and the relatively low supply and high demand for such workers: individuals are less willing to work somewhere that will place their health at risk, since that kind of sector demands more labour, wages increase. However, the reality is that the essential healthcare professionals who have served for years are being treated as lesser than these incentivized newcomers, who often have fewer qualifications.

In contrast to their low wage peers in the service sector, agricultural workers have not seen a pay boost or adequate personal protective measures. In both Canada and the United States, seasonal agricultural workers from abroad staff vast tracts of farmland during the summer. As early as April, while supervisors were given protective equipment, farmworkers in the United States reported that they were not being given any personal protective equipment. The problem is even more dire in Canada. Indeed, on June 16, Mexico temporarily forbade workers from entering Canada, after two temporary visa-holding Mexican farmworkers died from COVID-19-related complications. COVID-19 outbreaks have been reported on farms in Quebec and Ontario.

Mexico hits pause on sending temporary foreign workers after COVID-19 deaths https://t.co/6iN5aEt6U9 pic.twitter.com/uhbpoxhk1J

— CTV News (@CTVNews) June 16, 2020

Similar to farm labour, workers at the Albertan meat processing plant linked to the single largest outbreak in North America are often immigrants or temporary foreign workers. Meatpacking plants are notoriously dangerous for workers, yet conditions and wages remain poor. Once news of the outbreak spread, the government and the company responded with new safety measures to prevent the spread of COVID-19. But the question remains: Why hadn’t the plant adopted the same social distancing and safety measures as other sectors, like retail, which could not lock down? The clearest answer is that the workers are members of the relative surplus population: the plant is a machine for profit and more workers can always be found. In retail, however, employees interact with consumers, and thus, the move to protect their health and safety is linked to protecting the rest of the public.

What will COVID-19 do for race and class in North America?

The month of May returned surprising job gains in the United States and Canada, but the gains were not evenly distributed. African Americans returned to work at a lower rate than their white counterparts, owing at least in part to black-owned small businesses being less likely to receive support from the American government’s Paycheck Protection Program. Meanwhile, in Canada, the Emergency Response Benefit (CERB) has been criticized for helping low-income workers the least. On a more fundamental level, as some begin to move off the CERB and return to work, they can expect to earn less, working reduced hours at jobs on account of the virus.

Across North America, the uneven impact of COVID-19 on account of race, class, and gender has created growing dissatisfaction and unrest, leading many to ask what the post-pandemic world will look like. Some writers have drawn parallels to the Black Plague, during which worker scarcity drove wages up. However, this approach overemphasizes market forces. From setting higher minimum wages, to laws on competition, and from healthcare to public education, the most important factors in improving standard of living are in the hands of the government.

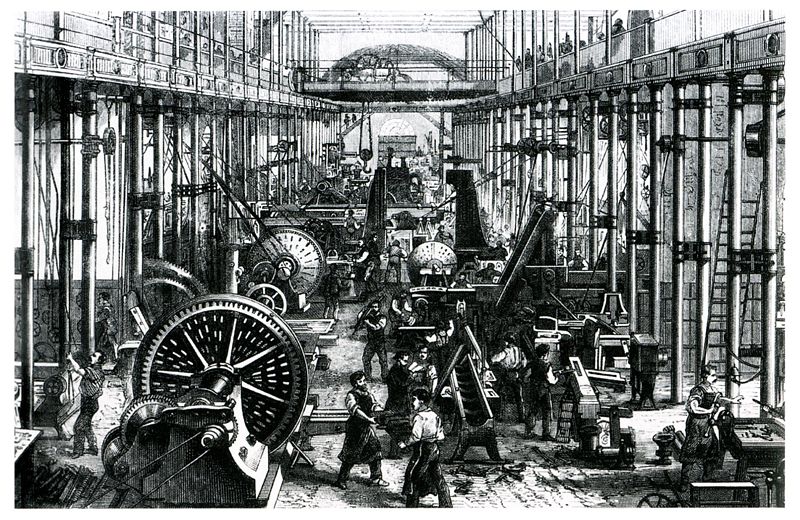

The feature image, “Sächsische Maschinenfabrik in Chemnitz, Germany, 1868,” is in the Public Domain. The working and living conditions of the urban poor in major cities during the Victorian era led multiple philosophers to question how such poverty could exist alongside great riches created by new technologies.

Edited by Sarah Farb

Notes

[1]Ian E. J. Hill, “The Rhetorical Transformation of the Masses from Malthus’s ‘Redundant Population’ into Marx’s ‘Industrial Reserve Army,’” Advances in the History of Rhetoric 17, no. 1 (January 2, 2014): 88–97, https://doi.org/10.1080/15362426.2014.886933.

[2] Iderley Colombini, “Form and Essence of Precarization by Work: From Alienation to the Industrial Reserve Army at the Turn of the Twenty-First Century,” Review of Radical Political Economics, December 12, 2019, 0486613419882124, https://doi.org/10.1177/0486613419882124.

[3] Hill, “The Rhetorical Transformation of the Masses from Malthus’s ‘Redundant Population’ into Marx’s ‘Industrial Reserve Army.’”

[4] Ibid.