Voting Patterns Are Not Immune to the Effects of Consumer Debt

Personal debt has gone politically unnoticed since the financial crisis but it has an underestimated effect on voting patterns, and it is only getting more powerful.

The winner of this November's election will need a strategy to cope with America's consumer debt. "United States Capitol building" by US Bureau of Land Management. Licensed under CC-0. http://www.publicdomainfiles.com/show_file.php?id=13948714211031

The winner of this November's election will need a strategy to cope with America's consumer debt. "United States Capitol building" by US Bureau of Land Management. Licensed under CC-0. http://www.publicdomainfiles.com/show_file.php?id=13948714211031

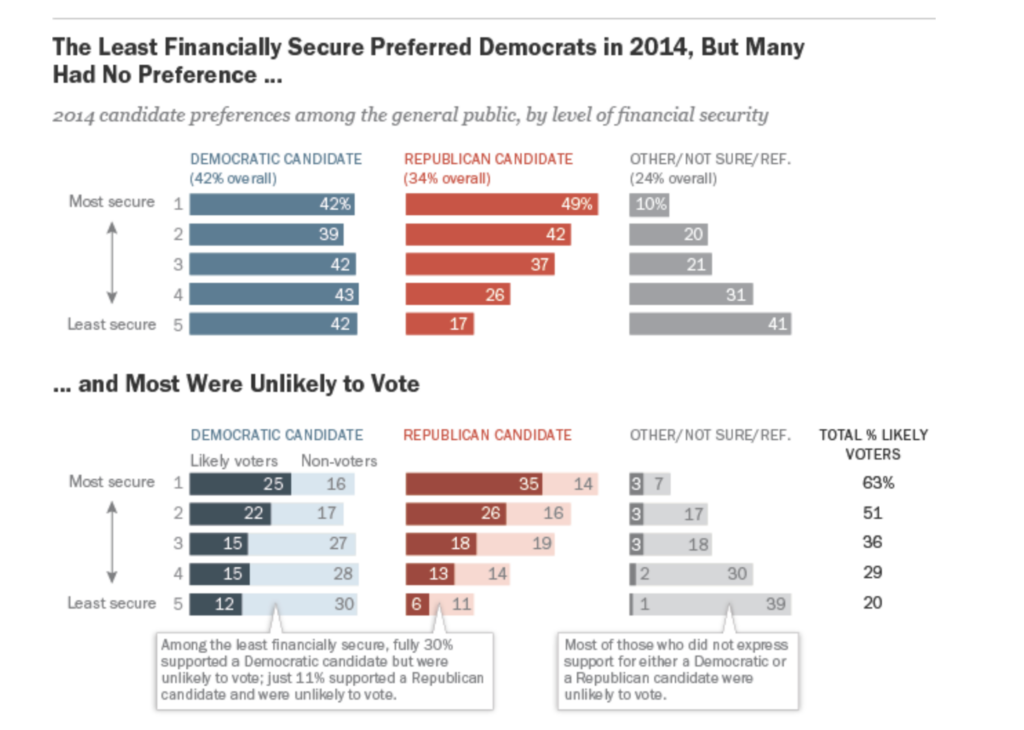

A conventional wisdom has developed in American elections: financially secure voters tend to support Republican candidates while less financially secure individuals vote Democrat. The Pew Research Center found that 49 per cent of those labelled “most financially secure” supported their Republican candidate, while support for the same candidate was only 17 per cent among the least financially secure. This can be explained by the following: affluent people are, in general, less supportive of expanding health care coverage and reducing wealth inequality, elements which rarely show up in Republican platforms.

But this pattern is, in fact, not a universal truth. It is nuanced and its strength varies from state to state causing many misinterpretations. Political pundits often criticize this model by claiming that richer states like Massachusetts traditionally vote Democrat and poorer states like Mississippi have voted Republican in every general election since Ronald Reagan was elected in 1980. In 2007, Fox News commentator Tucker Carlson famously claimed that “over $100,000 in income, you are likely more than not to vote for Democrats.” These criticisms, however, stem from a misunderstanding of income and financial security. Though they are often used interchangeably, one does not equate to the other. A voter who earns a high amount of money but is simultaneously crushed by student loans and medical payments is not considered financially secure. Personal debt, for many voters, is becoming a central political issue. Oversimplifying the prevalence of debt is a mistake, seeing as it comes in many forms, each with their own individual effect on a voter’s political preferences.

Unsecured debt, with a particular emphasis on student loan debt, is more likely to disengage a potential voter from participating in an election. Student loan debt now exceeds US $1.5 trillion spread across 42 million Americans and is growing rapidly. The increase in this type of debt does not combine well with the factors that in general motivate a person to vote: trust in the political system, inspiring leaders, marriage, and children. For instance, marriage and a stable family structure have proven to be a compelling motivation for many Americans to head to the polls. Raymond Wolfinger, a political scientist at the University of California Berkeley, conducted a study indicating that roughly 75 per cent of married people vote, while only half of singles do. Student loans, however, delay people from marrying and decrease a person’s likelihood of marriage altogether. Young people with student loans suffer from increased mental health stresses and are under pressure to work as much as possible, both of which can inhibit starting a family and thus keep someone excluded from the political process.

Students with debt also feel an increasing sense of political apathy and distrust in major political parties. Feelings that a single person’s vote does not matter are particularly common and stories of political corruption are intensely dissuading for student debtors. Fifty years ago, three in four Americans trusted the government to make the right decisions. Now, that trust is only at 19 per cent among millennials and college-aged voters. Meanwhile, the issues that students widely care about — affordable post-secondary education and the climate — were, until very recently, not a central issue during election cycles. Ultimately, these patterns contribute to student loan holders’ disconnection from the political process, harming their motivation to engage in elections. Student loans can effectively delay a person from voting and at times, reduce their belief in voting entirely.

The pattern of political disengagement among the least financially secure has significant implications for the 2020 election. Student loan debtors constitute a large chunk of those labelled as being “least financially secure”, whose absence in voting booths has had a considerably negative effect in particular for Democratic candidates. The rate at which potential voters lean toward a party, but ultimately refrain from voting is higher among potential Democrat voters. For instance, 42 per cent of the least financially secure support a Democrat ideologically, but only 12 per cent of them reported themselves as “likely to actually vote Democrat.” The discrepancy between ideological leanings and actual voting behaviour cost the Democratic party 71 per cent of their supporters within that group. As the following graph shows, this discrepancy is not as large when looking at Republican voters who are less financially secure. Student debt relief was an important topic during the Democratic primaries, and the next few months will show whether Presidential candidate Joe Biden has done enough to motivate this particular block of voters and ultimately reverse this trend.

Unlike student loans, certain types of personal debt are associated with higher political engagement. Mortgages and other secured debt — debt that is backed up by an asset like a house or a car used as collateral — works conversely to student loans in that it grants holders a personal stake in the political process. On both national and local levels, those with mortgages were more likely to vote. As a 2019 study from Stanford University found, homebuyers are 35 per cent more likely to vote in local primaries. Because this type of debt gives individuals a tangible incentive to involve themselves politically, voter turnout increases in all kinds of situations where voting is required, from local zoning issues to presidential contests. The explanation for the increased turnout is clear: after the 2008 financial crisis, mortgage debtors were wary of the housing market, so homeowners involved themselves in local political issues to protect the value of their investment. When considering the issues key to buyers, evidence shows that the items which increase the value of a home, such as zoning, schools and public safety, are the ones that spur political interest among homeowners. Mortgage debt does not only increase participation, but it also changes the type of participation encountered. Homeowners are intensely risk averse, meaning they support risk averse candidates, often members of the Republican party. In addition, homeowners tend not to embrace some of the policies at the forefront of the democratic agenda. For example, they seldom support the expansion of public housing projects, usually put forth by Democrats, as it does not benefit them directly. In the same vein, owning a home reduces the need for social insurance and thus large welfare programs suggested by Democrats garner relatively less support. In general, people with debt that is secured by collateral have less need for help from the government, which significantly affects their political decisions.

Large investments like houses and university degrees can make a voter both high income and financially insecure. It is the latter of those characteristics, along with the type of financial insecurity, that has a powerful effect on political preferences. Unsecured debt, which removes a person’s impetus to engage politically, decreases voter turnout among the least financially secure and damages the Democratic party. Nevertheless, secured debt encourages voters to participate and decreases the need for government intervention, consequently boosting Republican support.

Amid the global COVID-19 pandemic and severe unemployment, debt will play a pronounced role in the upcoming election. Tenants already struggle with paying rent and while many protections are currently in place, experts say a wave of mortgage problems is inevitable when these protections are lifted. Fewer jobs are available for college graduates and private loans are not covered by congressional relief efforts, meaning the student debt burden will not be eased. In short, an already influential voting factor is becoming more and more prevalent. Future elections will serve as evidence as to just how influential debt is on voters’ political decisions.

Featured image: “United States Capitol building” by the US Bureau of Land Management. Image under public domain.

Edited by Justine Coutu