What Democracy For Myanmar?

The Rise and Fall of Myanmar's Flawed Democracy

Osman’s name has been modified to preserve their anonymity.

On November 8, 2020, Myanmar, formerly known as Burma, held its third general election following the formalized transition from absolute military rule to a democratic electoral system in the early 2010s. Scholars and international observers alike welcomed the results as a catalyst for democratic consolidation in the Southeast Asian country. However, this ideal scenario came to an abrupt end; on February 1, 2021, the Tatmadaw, Myanmar’s Armed Forces, annulled the election results after contesting them for months. The ensuing coup d’état deposed re-elected State Counsellor Aung San Suu Kyi and President Win Myint, and revealed the long withstanding power of the military and the resilience of authoritarian politics in the country.

Myanmar at the hands of the Tatmadaw

In light of the 2020 general election that saw State Counsellor Aung San Suu Kyi’s re-election under the National League for Democracy (NLD), the Parliament of Myanmar was scheduled to convene on February 2, 2021, to formally swear in elected officials. However, in the early hours of February 1, as communication channels around the capital of Naypyidaw were interrupted, and widespread Internet disruptions were reported, the news that Aung San Suu Kyi and President Win Myint had been detained by the Tatmadaw broke across the country, along with the military’s declaration of a one-year state emergency.

General Min Aung Hlaing subsequently assumed the head of the Burmese state as Chairman of the State Administration Council and announced that Aung San Suu Kyi was being charged with breaching import-export laws related to the alleged possession of six unauthorized walkie-talkies. In response, Burmese people across the country and within the diaspora quickly mobilized to protest the coup and the resurgence of a military regime. Noisy acts of civil disobedience ensued, with people banging pots, clanging cymbals, and honking incessantly day and night, particularly in the capital city as well as the former capital of Yangon. Although such acts of civil disobedience may appear minor, they represent the unwillingness of the Burmese people to further tolerate the unforgivingly repressive stronghold of the military junta.

Social media has been an essential, privileged tool for Burmese grassroots activism in the wake of the coup. In the moments following Aung San Suu Kyi’s deposition from power, Burmese people took to social media platforms, mainly Facebook, Twitter and Instagram, to raise awareness for the ongoing political upheaval. Most notably, a workout video of a Burmese woman doing aerobics while military tanks rolled out in the country’s administrative capital Naypyidaw quickly went viral on Twitter, and became one of the first live images capturing the intense and unprecedented nature of the coup.

Unsurprisingly, it only took 24 hours for the military to announce a general ban on Facebook in Myanmar. Osman, a Burmese businessman in his early twenties currently residing in Yangon, nonetheless points to the younger generation’s resilience in the face of adversity: “We [the younger generation] are still able to access Facebook using VPNs [(Virtual Private Networks)], and we will not be silenced. People […] don’t want to get killed obviously, so our only platform for raising our voices is social media.” Osman later called for support to social media users across the globe, “Raise awareness as much as you can, just uploading stuff to your [Instagram] stories is already enough.”

However, the military response to the civil disobedience movement on social media was harsh and swift. On February 13th, the military government announced that new cyber laws would soon be imposed, further curtailing data privacy and access to social media, including telecommunications channels. They also announced that the state of emergency was amended to further restrict civil liberties, thereby granting them full authority to arrest individuals and search their homes without a warrant. Additionally, thousands of prisoners were released by the military into the streets of Tharkayta and Yangon, throwing “fire rings” and poisoning township water tanks. The increasingly violent and insidious nature of the coup has trapped Burmese people in a vicious cycle of dissent. This impromptu new chapter in the political history of Myanmar points to the anticipated collapse of a somewhat flawed democratic system in the country.

The flawed notion of democracy in Myanmar

The recent coup is yet another chapter in the tumultuous political history of Myanmar, which has experienced military rule and a widespread pro-democracy movement for several decades following independence. Aung San Suu Kyi, daughter of Burma’s founding father Aung San, who was assassinated in the months prior to independence, became the leading figure of the Burmese pro-democracy movement, and spearheaded the creation of the NLD party. As she became a more outspoken critic of the military regime and threatened to undermine “peace and stability” according to the junta, she was put under house arrest on-and-off for 15 years between 1989 and 2010. Suu Kyi’s fight for democracy in Myanmar solicited extensive international media coverage, notably earning her the Nobel Peace Prize in 1991.

In the subsequent 1990 election, the NLD won 81% of the seats in Parliament, a result which the SPDC soon annulled. The party later boycotted the 2010 elections, resulting in the victory of the military-backed Union Solidarity and Development Party (USDP). The 2012 by-election saw the rise of the NLD. The 2015 general election confirmed this apparent shift toward democratic values, with the NLD successfully winning and retaining 86% of the seats in the Assembly of the Union. Although the military drafted a clause in the constitution that prohibited Suu Kyi from becoming president as a result of her late husband and children being foreign citizens, the role of State Counsellor, akin to a Prime Minister, was created, and allowed her to assume the head of Burmese government. However, Suu Kyi’s rise to power marked the exposure of another dark chapter in Myanmar’s history.

Under the guise of democracy, domestic and national security affairs in Burmese politics were still very much shaped by the military junta. Any constitutional amendment seeking to reform this process is by default unachievable, as this would require 75% of the votes in the Assembly, a unity restrained by the presence of the USDP. Furthermore, the military government has long exerted pressure on Suu Kyi and the NLD to enforce the mass displacement and subsequent state-sponsored genocide of the Rohingya Muslim minority of the Rakhine state in western Myanmar. In this sense, the recent military coup poses yet another threat to the safety of the Rohingya in Myanmar, particularly in light of a repatriation plan proposed by Bangladesh — which has become the largest host country for Burmese Rohingya — in late January 2020.

The persecution of Myanmar’s Rohingya population adds to the list of illiberal practices that have gained attention since the NLD came to power. The arrest of two Reuters journalists by Myanmar’s security forces in December 2017, and their subsequent trial the following June, garnered significant international media coverage. Furthermore, a report from the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights later cited predatory policies that perpetuated a climate of fear and repression for journalists. This tainted picture brings much contrast to the simplified story of democracy in Myanmar, particularly in light of the democratic consolidation supposedly brought by the initial results of the 2020 general election. As foreign governments built their response to the coup on urging the military to restore democracy, the dominance of this simplified story is once again demonstrated on the international scene.

International sanctions: what future for Burmese people?

As the news of a military coup d’état in Myanmar reached the international community, U.S. President Joe Biden soon threatened to impose new sanctions on Myanmar in the name of “defending democracy,” although this stands in contrast to the U.S government’s historical neocolonialist interventions in much of the developing world. It is therefore unsurprising that President Biden would seek to intervene in the Burmese coup, despite evidence that sanctions usually harm the general population disproportionately more than the ruling political elites.

There is little evidence that the case of Myanmar will be any different. Past sanctions imposed on military regimes in the country did not incentivize the Tatmadaw to opt for democracy. In reality, they were only successful in solidifying wealth inequality and class divisions among regular Burmese citizens by worsening access to basic services such as health care and telecommunications.

Meanwhile, silence from Myanmar’s eastern neighbour, China, has been equally noteworthy. Hours after the coup was made official, Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesperson Wang Wenbin stated that China “hope[s] that all parties […] will properly handle their differences”, a response that pales in comparison to President Biden’s threats of sanction. However, China vetoed the United Nations Security Council the following day, citing concerns that international pressure on Myanmar would only worsen the situation. As Myanmar’s strongest economic partner and ally during the five decades of military rule, it seems rather unsurprising that China would seek to maintain this role as the Tatmadaw forcefully returned to power.

Regardless, there is little hope for the immediate return of a strong democracy in Myanmar. Waiting for a coordinated response from the international community, Burmese citizens have demonstrated remarkable adaptation skills in their civil disobedience movement. For Osman, this might represent the best hope to navigate the dark times ahead. “Hopefully there aren’t going to be too many repercussions from the international community. We need [foreign aid] type of support, […] if they impose sanctions on us, the only people that will be affected [are] the Burmese people.”

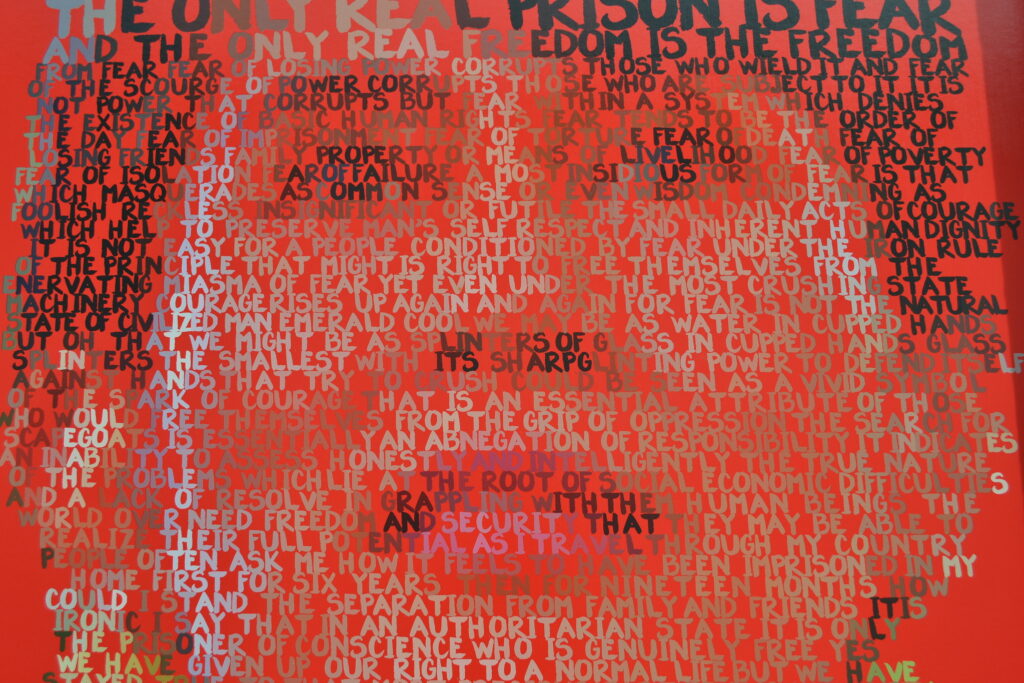

Featured image: “Aung San Suu Kyi mural, Vine Street” by Dom Pates is licensed under CC-BY 2.0.

Edited by Teresa Tolo and Chris Ciafro