What Islamic Extremism Says About French Secularism and Integration

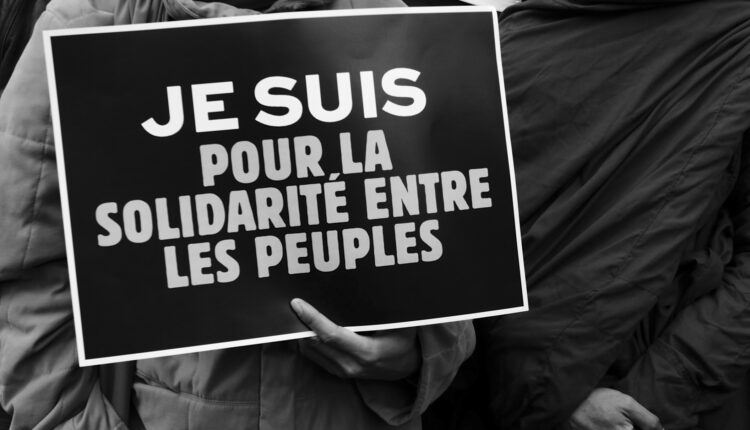

Manifestations in Paris following the murder of Samuel Paty. This picture taken by Olivier Ortelpa is licensed under CC by 2.0.

Manifestations in Paris following the murder of Samuel Paty. This picture taken by Olivier Ortelpa is licensed under CC by 2.0.

In the past few years, France has experienced several terrorist attacks led by Islamist extremists, the most recent occurring within weeks of each other last month. On October 16, a suburb of Paris saw the horrific decapitation of middle school teacher Samuel Paty by eighteen-year-old extremist Abdoullah Anzorov in response to the teacher’s use of caricatures of the Prophet Muhammad in a class on free speech. In Islam, visual depictions of the Prophet are strictly forbidden, hence many Muslims’ anger regarding the use of these mocking portraits. One of France’s core principles is “laïcité,” or secularism, which strictly separates religious and governmental affairs, something Paty strongly believed in. He used the illustration of the Prophet to teach his students about “laïcité” and freedom of expression, the second of which includes the right to make blasphemous statements about any religion.

Instructing immigrants with different belief systems through the “instilling of the nation’s core values,” including that of “laïcité,” is France’s established technique for social integration, although recent events have led to skepticism regarding its effectiveness. Over the last few years, the rise in terrorist attacks could be linked to this approach, with some perceiving it as the government’s forced assimilation to conform to the white Catholic culture of the “typical” French person. Attempting to instill secular values has led this manner of integration to be labelled as xenophobic, considering that it essentially pressures Muslims to decide between their religion and fitting into French society. Even native French Muslims often feel like outsiders, as racism and Islamophobia are continuous obstacles preventing them from truly integrating socially.

The actions taken by Anzorov are not a one-time occurrence; they follow a string of other similar terrorist attacks, one being a shooting at the satirical newspaper Charlie Hebdo’s offices in 2015 — also motivated by the publishing of caricatures of the Prophet Muhammad — that left 12 of their staff dead. Later that same year, the Parisian Bataclan theatre suffered the most deadly attack in recent history, resulting in 130 deaths and hundreds of wounded. More recently, Paty’s murder was followed by another knife attack in Nice’s Notre-Dame basilica on October 29. The repetition of such events is part of a larger pattern of Islamic radicalization in France and reflects largely on Muslims’ treatment within the nation. Increased hostility towards Muslims in the aftermath of attacks only exacerbates the social isolation they face, as most live in already alienated poorer suburbs, known as “banlieues.” The connotation that this particular term has in France does not only express the economic status of these neighbourhoods, but has become derogatory and racialized in implying that these are “slums dominated by immigrants”, and in particular those of Muslim descent. The “banlieues” are often concentrated districts of poverty and social segregation, and much of the general population in France believes that they are responsible, even if only partly, for the numerous killings in recent years. While this is a radical generalization that only further stigmatizes Muslim immigrants and natives, the constant isolation and racism faced by the banlieues’ inhabitants can push some towards radicalization, as seen in the orchestration of the Bataclan attacks.

France’s rigorous adherence to secularism has led to controversy regarding where the line should be drawn between freedom of speech and freedom of religion, as violent extremist action seems to only be escalating. While some groups of Muslim leaders have spoken out in support of “laïcité,” stating that it is “essential to allowing different religions including Islam to flourish in France,” the government’s recent public comments on the attacks and Islam as a whole have also incited negative responses from Muslim communities, both nationally and worldwide. President Macron denounced the religion as being “in crisis all over the world today,” presenting several new measures aiming to protect ‘”laïcité.” There have additionally been controversies surrounding the allowance of Islamic practices in public places, such as women wearing the hijab or the training of imams in local facilities, due to a belief that it goes against the nation’s secular foundation. Macron has stated that the impact Islamic fundamentalism has had on public institutions would be reduced through the implementation of severe limits on homeschooling, religious schools, and associations. As all of these have been places where radicalization might have been promoted in the past, the government feels that a strict crackdown on these forms of education would aid in countering Islamic extremism in the country. While such laws would apply to all religions, Macron is of the opinion that “Islamist separatism” has posed a more pressing threat than others as it “holds its own laws above all others and often results in the creation of a counter-society.” Professors at different French universities who have spoken on the subject believe the introduction of restrictive secular laws is aimed a lot more at “cleansing society of immigrants and Islam” than anything else, and will simply result in the increasing isolation of the millions of French Muslims peacefully living in France.

The French government’s response to the recent attacks has inflamed relations with Muslim majority nations, bringing about retaliatory comments as well as a boycott of French products. Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan stated that Macron must have “lost his mind,” and nearly every Muslim majority country in the Middle East has followed in Erdoğan’s footsteps, either with similar statements in response, such as that from Iranian Foreign Minister Javad Zarif, or through demonstrations of their own. Iraq, Lebanon, Jordan, and Saudi Arabia have all publicly condemned the publication of the caricatures, while civilians in Syria, Libya, and Egypt have taken to the streets to protest Macron’s decisions. This amount of backlash will undoubtedly have an impact on the French economy and future political relations unless leaders agree to peacefully discuss the situation soon.

Muslims are the primary victims of the "cult of hatred"—empowered by colonial regimes & exported by their own clients.

Insulting 1.9B Muslims—& their sanctities—for the abhorrent crimes of such extremists is an opportunistic abuse of freedom of speech.

It only fuels extremism.

— Javad Zarif (@JZarif) October 26, 2020

Disintegrating these international relations also affects French Muslims, who already face poor treatment. With some mosques and Muslim aid organizations being forcibly closed down and facing undue criticism, such as the Collective Against Islamophobia, which was labelled “an enemy of the republic” by the Interior Minister, the marginalization of this group is only increasing. Out of the six million Muslims living in France, nearly all of them are peaceful citizens wanting to practice their religion like any other, and the pressure to defend their practices — when risked with losing them — is causing a divide between their community and others, which can push them even more towards radicalization.

A solution to the current situation would be complex, as a fair balance must be found between expression, religion, and secularism, and also requires the deconstruction of a pattern of isolation and racialization currently faced by French Muslims, neither of which will be easily achieved. The current environment, both in France and internationally, is not conducive to peaceful discussion regarding its resolution. Nonetheless, the situation today seems to be rooted in much deeper systemic issues within the French system, especially in its ability to ethically and respectfully integrate citizens and non-citizens alike while upholding its secular values.

The featured image by Olivier Ortelpa is licensed under CC by 2.0.

Edited by Selene Coiffard-D’Amico.