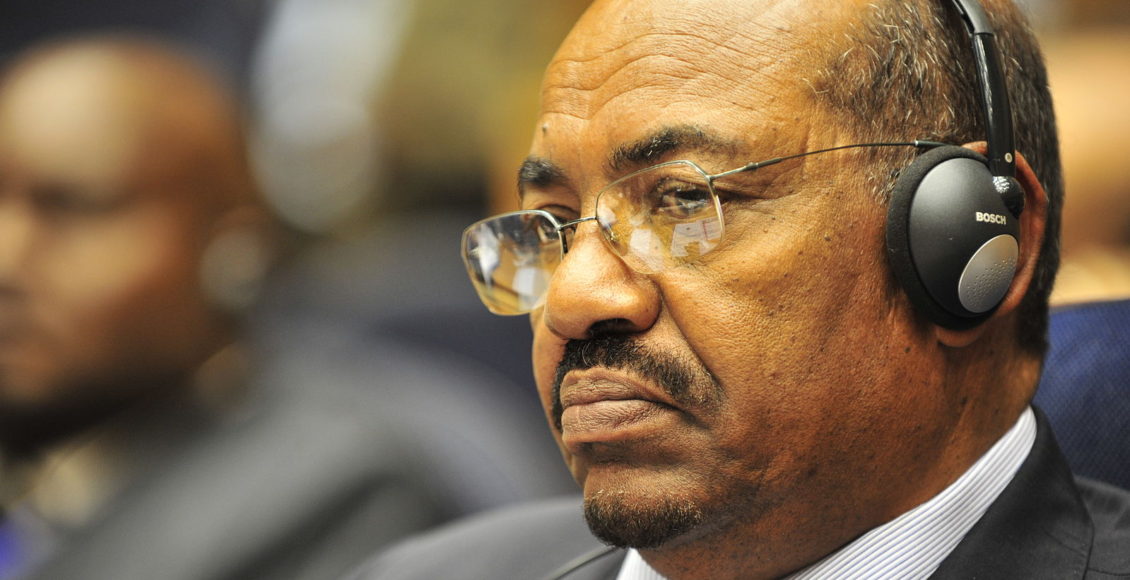

What Lies Ahead for Sudanese President Omar Hassan al-Bashir?

This week marked the six-week anniversary of nation-wide demonstrations in Sudan against the current regime of President Omar Hassan al-Bashir.

Beginning on December 19th in response to Bashir’s termination of fuel and wheat subsidies, the demonstrations have quickly morphed into a movement calling for Bashir’s resignation.

In recent weeks, the President has become increasingly reliant on violent tactics to quell the movement. This past Thursday clashes between protestors and the police in Khartoum lead to the death of three protestors, including a doctor and a child. As of last week, human rights groups claim that at least 40 people have been killed during demonstrations.

These protests, while substantial, are by no means the first threat to President Bashir’s authority. Since coming to power through a military coup in 1989 that deposed the democratically elected government of Prime Minister Sadiq al-Mahdi, President Bashir has faced repeated internal and external challenges to his political legitimacy. Throughout them all, however, Bashir has proved to be remarkably adept at maintaining a firm grip over Sudan despite such threats.

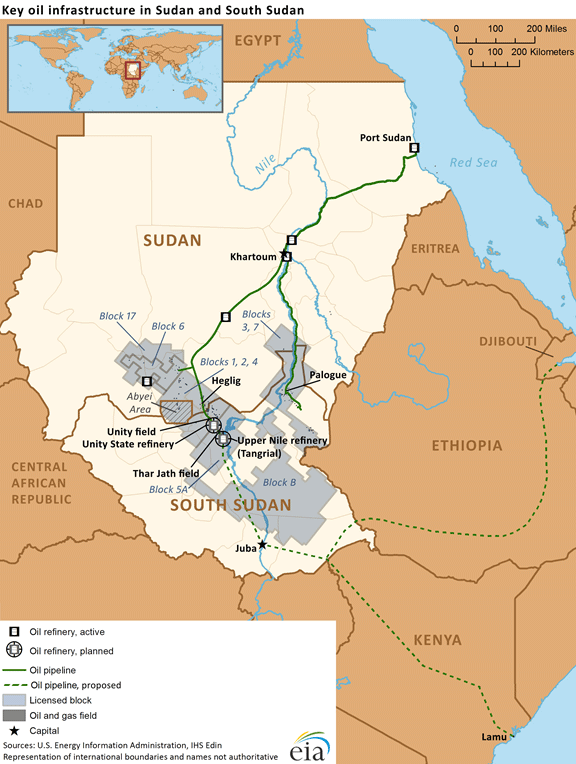

On the domestic front, Bashir’s Sudan has been wrought by internal conflict stemming from disputes over power and wealth sharing between the center (Khartoum) and its much larger peripheries. When Bashir came to power in 1989, Sudan was already five years into a bloody, costly civil war in the south after the Sudan’s People Liberation Movement (SPLM) revolted against al-Mahdi’s government in 1983, citing inequity between Southern and Central Sudan as well as fears of the growing Islamist character of that state. The people of Sudan would not see an end to hostilities in the south until 2005 with the signing of the Comprehensive Peace Agreement (CPA) between both parties. While originally meant to foster unity between the South Sudan and Sudan-proper attractive, provisions for a South Sudanese referendum on independence lead to the establishment of South Sudan as a new state on July 9, 2011.

Although this move served to eliminate the “Southern Question”, a key source of conflict in the country, in its wake arose a number of ancillary disputes. For starters, tensions resulting from the failure to resolve many post-secession issues prior to formal partition led to a period of continued conflict between both countries along the Sudan-South Sudan border. In addition, the secession of South Sudan has made Sudan less open to giving further concessions in territorial disputes with the Blue Nile and South Kordofan states, Abyei, and Darfur – a dispute which began in 2003 and has led to President Omar al-Bashir’s conviction in the International Criminal Court (ICC) of charges related to genocide, war crimes and crimes against humanity.

These conflicts have exacerbated Sudan’s overall volatility, preventing the state from achieving long-term economic and social stability and the levels of economic growth and poverty reduction that accompanies such cohesion.

Moreover, in terms of external challenges, Sudan under Bashir has endured debilitating economic, financial and trade sanctions by the United States since 1997 due to the country’s designation as a state sponsor of terror. These sanctions have prevented Sudan from fully integrating with the global economy and delimited the extent to which the country can attract foreign direct investment, two factors which have only compounded the country’s already fragile debt burden.

Despite these challenges, however, Bashir’s absolute dominance over Sudanese political life has shown no signs of abatement. This fact was made abundantly clear after the events of Sudan’s last major protests: the 2011-3 Sudanese Intifada. Taking its cue from the wave of revolutionary uprisings occurring across the Arab world in 2011, the Sudanese Intifada erupted in response to austerity measures imposed by the Bashir regime in order to counterbalance lost oil revenue stemming from South Sudan’s secession in early 2011. While protests were substantive, in this instance, Bashir was again able to weather the storm by detaining and torturing as many suspected protestors as possible in order to quell the demonstrations.

What then, should we make of these current protests? Specifically, should we expect them to be any different from those of the past?

On one hand, we might be consoled by the distinctiveness of the current protests. Unlike previous protests that have racked Sudan, which have largely been confined to the capital Khartoum, the current movement represents a much broader demographic.

Unfortunately, however, this fact in and of itself will not be enough for Sudan to witness the change its protestors are seeking. Indeed, any analysis of the potential efficacy of the protests must also recognize the many obstacles that stand in the way of a Bashir-free Sudan.

First, it is important to recognize the extent to which Bashir, through his divide-and-rule tactics, has completely abrogated his responsibility to ensure the proper development of Sudanese political life. Thus, while Bashir himself is in a vulnerable position, there is no obvious figure from either the government or the opposition to replace him as was the case in Egypt and (eventually) Yemen during the 2011 Arab Spring. In light of this, it is highly unlikely that Bashir and his National Congress Party (NCP) will voluntarily cede their authority any time soon.

Others have mentioned the possibility of a military coup similar to the one that brought Bashir to power in 1989 as another potential outcome of the protests. While there are merits to this line of reasoning, there are also notable faults. Specifically, such arguments neglect the extent to which Bashir has effectively ‘coup-proofed’ his regime since coming to power in 1989. Bashir, aware of the mistakes of his predecessors, has worked diligently to establish parallel security organizations in order to counterbalance the authority of the army. Moreover, while there are middle- and lower-ranking officers in the army who are dissatisfied with such moves, Bashir has been able to offset these concerns by extending new lines of patronage to elements of the top brass. Consequently, since the protests began, the military has repeatedly stated its support for the country’s leadership.

Finally, the international environment has nearly obliterated the prospect that these protests might institute any substantive change to Sudanese political life. Both Egypt and Saudi Arabia have no desire to see President Omar al-Bashir overthrown. Egypt’s President Abdel Fatah al-Sisi, having himself taken power in 2013 after a military coup against former Egyptian president Muhammad Morsi, would see such a development as a direct threat to his own legitimacy within Egypt. Saudi Arabia, while sharing a similar concern, is also preoccupied with the sizeable investments it has made in Sudan in response to Sudan’s decision to participate in the Saudi-led coalition against the Houthi insurgency in Yemen.

Support for the al-Bashir regime, however, is by no means limited to regional allies. European Union (EU) member states, seeking to limit the influx of African migrants cross the Mediterranean into Europe, have relied upon Sudan to combat irregular migration, migrant smuggling and human trafficking in exchange for its implicit backing of the regime.

Moreover, over the past couple of years the United States has also become increasingly reliant upon the al-Bashir regime’s cooperation on counterterrorism operations. Consequently, in 2017 the United States moved to lift the sanctions it placed on Sudan in the late 1990s under the Clinton administration.

Beyond these individual concerns, however, both the United States and Europe view the stability of Sudan as paramount to preventing the type of power vacuum that has engulfed Libya, Syria and Yemen in the aftermath of the 2011 Arab Spring and has given new impetus to global-jihadi Salafist organizations such as al-Qa’ida and Daesh.

Thus, for the time being, its seems as though President Omar al-Bashir is here to stay. This fact is especially frustrating when one considers the extent to which these protests have shown the world that the people of Sudan are tired of the status quo. However, we should take solace in the fact that history is never preordained. It is entirely possible that some future event might fundamentally alter the course of the current demonstrations. It also very well may be that the above calculations are prefaced upon false assumptions and that the current protests will in fact be successful.

Only time will tell.

Edited by Sarie Khalid