Russia’s Revolution? Alexei Navalny’s Opposition

Why Alexei Navalny’s Opposition Movement is Stronger than Ever

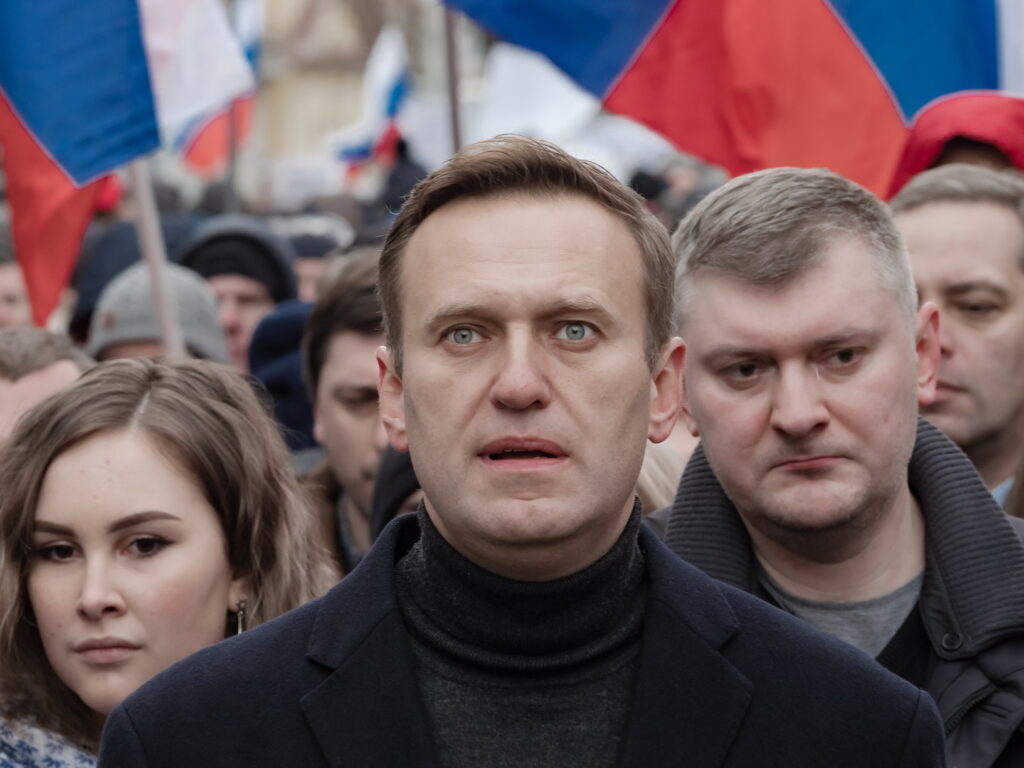

Opposition leader Alexei Nalvany and wife Yulia Navalnaya marching in July 2020. “Sun in the flags of protesters” by Michał Siergiejevicz licensed under CC BY-NC 2.0.

Opposition leader Alexei Nalvany and wife Yulia Navalnaya marching in July 2020. “Sun in the flags of protesters” by Michał Siergiejevicz licensed under CC BY-NC 2.0.

Of the many weapons designed during the Cold War, Novichoks are some of the most insidious. They are a group of nerve agents, many times more deadly than similar poisons like sarin or VX gas, and a signature weapon of Russian intelligence services. It was a twist of fate when Alexei Navalny, Russia’s most prominent opposition leader, lived to tell the tale after he was poisoned with Novichok on August 20, 2020. Navalny’s brush with death, subsequent return to Russia, and recent arrest have ignited protests as fierce as any Russia has seen since the fall of the Berlin Wall. This time, opposition figures have the opportunity to sow the seeds of defiance that could lead to concrete political change in the future.

Alexei Navalny has proved to be a difficult and determined opponent for the Kremlin. Due to his political activism dating back to 2000, he has been jailed over ten times, spending numerous months in prison and under house arrest, most notably for his role in the 2011 Russian protests. Over his career, he has emerged as by far the most well-known and vocal critic of Putin’s rule. By August 2020, it seemed as though the regime had decided to end Navalny’s ascent. On a flight from Tomsk to Moscow, Navalny collapsed and was taken to a hospital following an emergency landing before being flown to Germany for further treatment. After his recovery from a coma and a long stint in the hospital, he returned to Russia in 2021 to resume his role as a thorn in Putin’s side. The protests that have erupted since his return have featured thousands of Russians spread across political lines in the country. The roots of a successful opposition are to be found in widespread changes in Russia that have the potential to ever so slightly tilt the balance of power away from Putin.

2011

Commentators often tout the current protests as the largest in a decade, directly comparing them to the 2011-2013 riots. Sparked by the results of the 2011 legislative election, Russians took to the streets that year, primarily demanding free and fair elections, which became a signatory phrase. Vladimir Putin, at the time Prime Minister, announced an agreement with then President Dmitri Medvedev to run for the presidency, fuelling protesters’ anger. The protestors’ frustration, however, was chiefly directed at election officials and called for the freeing of political prisoners, the annulment of the election results, and an official investigation of voter fraud, among other claims. The protests gained some concessions from President Medvedev, including direct elections for governors and a reduction in the number of signatures needed to run for the presidency. Putin, however, derided the protests as the work of US agents, singling out Hillary Clinton by name, and tightened his control over Russia upon his return to power. The contrast in the prospects of Russia’s opposition from 2011 to 2021 is stark, and shows that Navalny and other protestors have reason to be hopeful.

How Navalny is repairing a fractured opposition

For much of Russia’s recent history, friction between opposition groups was almost as much of a hindrance to their effectiveness as the Kremlin itself. Accusations and sparring between opposition groups allowed to run in elections and those banned by the regime were widespread. In 2018, Ksenia Sobchak, a celebrity TV anchor and close family friend of Putin, ostensibly ran for the presidency as an opposition candidate. Given she had the Kremlin’s blessing to do so, her candidacy was considered by some to be an attempt to undermine Navalny’s campaign, splitting liberal voters. However, the vast worldwide media attention generated by Navalny’s poisoning and arrest over the past several months has pushed the opposition leader past other smaller candidates and formed a broader, more united coalition. Alexandra Arkhipova, a social anthropologist in Moscow, interviewed Russian protestors in January and found that 42 per cent of those surveyed had never protested before. Attracting Russian citizens who were less politically engaged or motivated as well as commanding the support of the existing majority has been a key driver of the massive numbers of protestors seen across the country. The fracturing of Russia’s opposition groups has diminished since 2018. Recent programs such as Navalny’s “smart voting” project have attempted to unite the various elements of the opposition wing of Russian politics and throw support behind candidates with the best chance of beating Putin’s United Russia party. This strategy was used to great effect in the 2019 Moscow city council elections, where 20 of 45 positions on the Moscow city council were captured by opposition candidates. These developments put Navalny in the perfect position to mobilize large swaths of the country in opposition to the United Russia party.

The screening

As with everywhere else in the world, the prominence of Youtube, TikTok, Instagram, and other social media channels has grown in recent years and now form a major element of Navalny’s political strategy. The masterwork to date has been “Putin’s Palace,” a documentary detailing a palatial estate allegedly owned by the President. Key details such as the supposedly $850 USD toilet brushes have stuck with the public consciousness and have been adopted as protest symbols of their own. The opulence detailed in the documentary as well as the calls for protests on January 23 struck a chord with many Russians. Since its posting two weeks ago at the time of writing, the video has been viewed over 110 million times.

Social media has also been an increasingly popular outlet for Navalny, whose own personal social media presence on Twitter and Instagram boasts a combined 6.5 million followers that rivals that of the largest Russian news media outlets on the platforms. The increased diversification of social media has also spread online movements across different platforms, portraying a stark difference from protests in 2011 that relied chiefly upon Facebook as a medium for their planning and communication. This has made information harder to suppress, as Russian authorities have been confronted with a host of different sites to tackle. Newer sites such as TikTok or Telegram are also increasingly popular, leaving Russian authorities steps behind in their censorship, though they are persistent in their attempts to suppress information. The Kremlin has retaliated against online information about protests by legislating restrictions based on age. Minors cannot be encouraged to attend protests under Russian law — up to 38 per cent of TikToks, 50 per cent of Youtube videos, and 17 per cent of Instagram posts mentioning Navalny and unrest were removed from the sites, according to Roskomnadzor, Russia’s media regulator. Much of this battle is a fight over the activities of younger Russians, a cohort that is both much more likely to support Navalny and have a significant online presence.

Liking their chances

Worldwide events are more favourable for Russian dissidents now than they were ten years ago. Changes to the pension plan for many Russians in 2018 have turned some older people and pensioners, previously a reliably pro-Putin group, against the regime. Worsening US sanctions and slumping oil prices have worsened thousands of Russian’s real incomes over the past several years. Similar to the ripple effect of the Arab Spring protests in 2011, demonstrations in Belarus and Siberia in 2020 have mutually reinforced protests in Moscow. However, for now, the protests have quieted amidst calls to turn out and vote in the fall parliamentary elections, and increased the pressure on Europe, the US, and Canada to sanction Russian leaders. Putin can ignore Navalny for as long as he likes, but the opposition leader is biding his time and the threat he poses to the Kremlin is greater now than ever.

The featured image, “Sun in the flags of protesters” by Michał Siergiejevicz, is licensed under CC BY-NC 2.0.

Edited by Alua Kulenova