Bangsamoro: Power Politics and Governance in Southern Philippines

Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte (left) and MILF leader Murad Ebrahim (right) have a vested interest in the success of the Bangsamoro Autonomous Region. (image credit: Alec Regino)

Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte (left) and MILF leader Murad Ebrahim (right) have a vested interest in the success of the Bangsamoro Autonomous Region. (image credit: Alec Regino)

Earlier this year, Mindanao, the Philippines’ southern region, held a two-part plebiscite on January 21 and February 6 on the creation of the Bangsamoro Autonomous Region (BAR) in Muslim Mindanao. With an 85% voter turnout and a resounding Yes vote (87%), the message was clear: the people of Mindanao, tired of half-a-century of conflict, are ready for a change.

The newly ratified region is designed to replace the Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao (ARMM), the existing political framework established in 1989 to grant self-governance to the Bangsamoro people. The Bangsamoro, or “Moro” people are an amalgamation of various ethnolinguistic groups who predominantly practice Islam in Mindanao. For 30 years the Moro people have had the option to participate in the watered-down ARMM system, where rampant corruption, mismanagement, and a disingenuous autonomy weakened their capacity to self-rule. Shortly after its implementation, the ARMM’s popularity wavered within the region and across the nation and by 2011 the ARMM was labeled by the Philippine government as a “failed experiment.”

The issues of Moro autonomy and the failure of the ARMM are matters that President Rodrigo Duterte has a vested interest in. As the first Filipino President to hail from Mindanao, Duterte’s platform has rested primarily on drug abuse eradication and anti-Manila imperialism. While plenty has been justly stated on the former, it’s Duterte’s unique position on the latter plays an important role in the ratification of the BAR. The creation of the Bangsamoro region marks a significant victory for the Duterte administration, considering that Bangsamoro will serve as a test case for federalism— Duterte’s proposed form of governance for the nation.

Prior to his presidency, Duterte expressed concern against government administrators attempting to address issues in the region who he says, “are not from Mindanao, who do not have [an] in-depth understanding of how we live here, our problems and how we solve them.” Unsurprisingly, his perspective resonates with the Muslim minority in the Philippines, a group that has faced an enduring history of discrimination due to deep-rooted prejudice and forced resettlement programmes under a predominantly Christian government rule. Duterte grasps the depth of Muslim alienation in the Philippines unlike conventional politicians in Manila, making him a vital element to the Bangsamoro peace process. It was him, after all, who pushed a reluctant Congress to pass the laws that laid the groundwork for the plebiscite.

While the BAR is a promise for a better future for Bangsamoro, Mindanao still faces an uphill battle for a sustainable resolution on this 51-year conflict. Although the BAR is meant to address issues with the ARMM, power politics will consequently shape the future of governance in Southern Philippines. In other words, familial clans vying for power and Moro rebel organizations, such as the Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF) and the Moro National Liberation Front (MNLF), are key players that will determine the success of the BAR. The aims of these various groups and of President Duterte is not as simple as a choice between war and peace.

The MNLF and MILF: Between Independence and Autonomy

The contemporary manifestation of the separatist conflict in the Philippines can trace its origins back to at least 1968, with the establishment of the Muslim Independence Movement following the appalling slaughter of Moro soldiers in Corregidor island. Initially dominated by traditional Moro elites, the organization splintered in 1972 due to a clash in ideology between established elites and younger, secular student leaders. These college activists, led by Nur Misuari, established the MNLF to aspire towards an independent state through Moro nationalist rhetoric, emphasizing openness towards non-Muslims in Mindanao. The MNLF enjoyed early success, receiving widespread support from various Moro groups and utilizing guerrilla tactics to establish authority in the southern islands. By 1976 the MNLF, with mediation from Muammar Gaddafi, signed the Tripoli Agreement with the Philippine government under the promise of greater autonomy in the region.

Despite the planned peace deal, disagreement on the implementation of the agreement stalled negotiations and fighting quickly resumed. In the meantime, the MNLF faced an internal leadership crisis: Misuari’s command of the organization was largely autocratic and centralized, but within the MNLF some members preferred consultatory collaboration and convergence towards more Islamic ideals. Not long after the collapse of the Tripoli Agreement the MNLF fractured into an assortment of groups with differing ideologies. One of these groups, the MILF, sought an independent Islamic state for the Moro people. Today, they are the most influential independence group in Southern Philippines and the main organization Duterte has cooperated with on the establishment of the BAR.

Throughout the last five decades the Philippine government has attempted to negotiate peace deals with all these groups, seeing limited success. The proposed BAR is supposed to be different, but a main point of concern is whether Duterte and the MILF will be able to get other groups to play ball. Segments of the MNLF were integrated within the now-defunct ARMM, and Misuari served as its governor from 1996 to 2001. Peace talks between the MILF and the government caused leadership within the MNLF to believe that their organization had been sidelined. In response, an MNLF faction attacked Zamboanga City in 2013, with Misuari declaring a short-lived independence from the Philippines. Duterte hopes to discuss the Bangsamoro peace process with Misuari, who he has described in the past as a “good friend.” Misuari has remained silent for now, but that hasn’t stopped violent clashes between MNLF and MILF members that have occurred after the plebiscite. While the ratification of the BAR represents a general consensus on how the Moro people wish to be governed, it is critical that Duterte and the MILF actively consider the motives of other regional self-determinism groups that have a stake in the success (or failure) of Bangsamoro.

Additionally, the MILF will have to mitigate the impact of radical militant groups who exploit anti-Manila sentiments and ineffective governance to bankroll their own devastating agendas. Terror groups such as the Abu Sayyaf, who have been accused of planning the bombing of a cathedral in Jolo last month, and the Maute group— who sieged the city of Marawi for five months in 2017— are also potential roadblocks to peace. A successful BAR is likely to weaken their influence in Mindanao, while another failed Bangsamoro peace talk could embolden support for their cause. The successful implementation of the BAR is crucial to the eradication of terror groups, as a strong governing body would be able to control the distribution of firearms and cut their access to external suppliers. Carrying the BAR framework through to achieve this aim, however, may also face resistance from another power player: family dynasties unwilling to cede substantial control of Mindanao.

Power Runs in the Family: Clan Politics in Bangsamoro

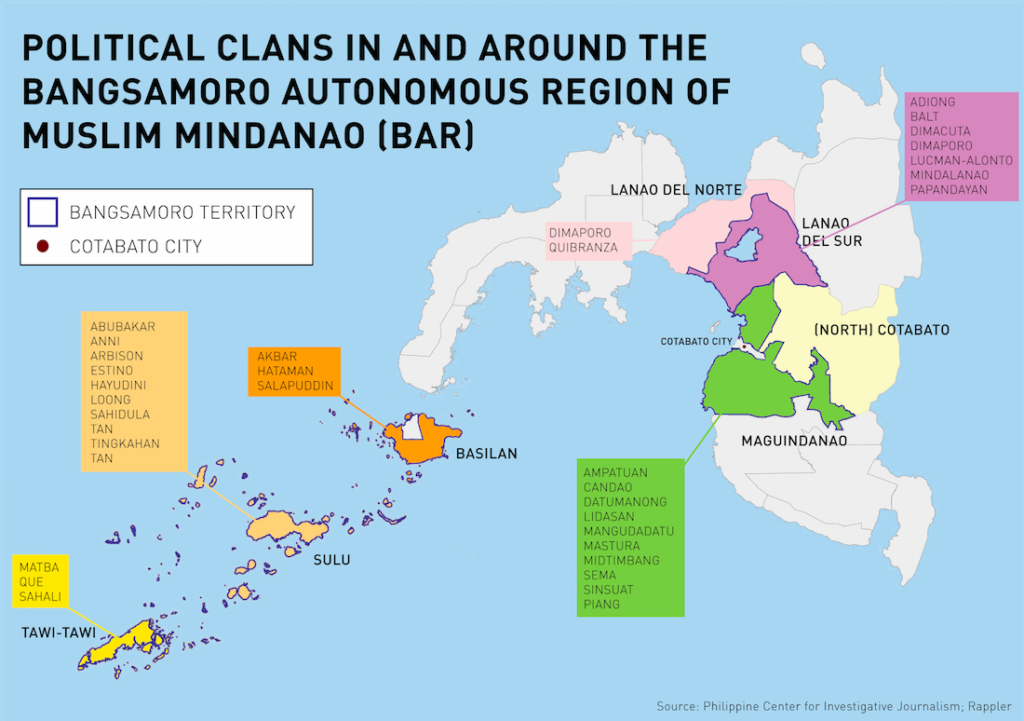

Within and around the new BAR are a handful of historic political clans who hold seats in key government positions and maintain an oligarchy on business. Their varied positions on Bangsamoro hold strong implications on its solvency. In Cotabato City— the longstanding de facto capital of the ARMM— the campaign for ratification was largely perceived to be a political competition between clans. Mayor Cynthia Guiani Sayadi opposed the city’s inclusion in the BAR, to an extent where pro-BAR residents felt afraid to express their support. In the first plebiscite, the city’s residents ultimately voted to ratify Bangsamoro. Sayadi claims that the Armed Forces of the Philippines conspired with the MILF to ensure the BAR’s ratification. The army has denied these claims.

Meanwhile, in Lanao Del Norte, the Dimaporo clan allegedly led a disinformation campaign against the BAR, fearing that a loss in territory would weaken the province. Their distrust stems from the protracted conflict with the MILF, who have attacked Lanao Del Norte multiple times in the 2000s. Despite returns that show that six towns voted to join the BAR, all were overruled by voters in the rest of the province. For these areas, inclusion in Bangsamoro required a majority to be reached from both the towns themselves and the other 21 towns in the province.

The opposite transpired in Sulu, where a majority of residents rejected Bangsamoro law but will still be a part of the new BAR. Prior to the vote, Governor Abdusakur of the Tan family criticized the Bangsamoro law, citing the unconstitutionality of dismantling the ARMM and argued that the vote in itself denies their local autonomy. The plebiscite considered the ARMM as a single geographic region, prompting pre-existing provinces in the ARMM to vote as a single bloc. Sulu, as a part of the ARMM, had its votes nullified by residents from other provinces.

As demonstrated in the map above, there are many influential clans in the region. Alongside the aforementioned, all have the ability to influence constituents in their area and will likely participate in the elections for seats in the Bangsamoro Transition Authority (BTA), the BAR’s new parliamentary system. It’s hard to say how the MILF and the Philippine government plan to engage with these families, but their role in the future of the BAR cannot be understated. In the past, clan politics debilitated the already limited ARMM’s capacity to successfully govern. For instance, while violence in Mindanao is generally attributed to ethnoreligious tensions between Muslims and Christians, a large number of these incidents find their roots in violent disagreements between warring clans, or “rido”. In 2009 tensions caused by an upcoming gubernatorial election provoked the Ampatuan family to use their private army to murder a convoy of 58 people on their way to witness a member of the Mangudadatu family file for candidacy. Human Rights Watch estimates that there are about 100 private armies operating all throughout the Philippines. The question remains how, if at all, can MILF cease rido between ruling clans and if the creation of the BAR will cause MILF to be at odds with these powerful families. If these clans are unwilling to share power amongst each other, it is difficult to see them peacefully governing alongside former rebel groups that most have clashed with over the last five decades.

A Future for the Bangsamoro People

While there are a lot of players vying for power in the new BAR, the component essential to the success of this region is the Moro people themselves. Through their vote earlier this year, they have already displayed their ability to dispense a collective identity and moral solidarity to redress historically unresolved issues. This unity has the power to transcend the influence of opportunistic power players in the region. The MILF may hold a majority in the BTA up until 2022, but the Bangsamoro people definitively select who gets the opportunity to represent them. If the democratic process fails, they make decisions on how to respond. They hold the power to keep corrupt politicians in check, to endorse policy proposals for the betterment of society, and to resist coercive forces that drags Bangsamoro down. Independence movements, influential families, and terror organizations are nothing without people to support their plays for power.

Ultimately, passed “solutions” to the issues that plague the Southern Philippines have failed because the Philippines’ governmental practices are plainly based on a premise that not everyone should govern. Memories of an antagonistic relationship between the people of Mindanao and lawmakers in Manila have led to a patronizing perspective of regional problems, producing inadequate results. The Moro people, however, have and will continue to devise strategies in which they can choose how they should be governed. In an elaborate and contentious subject like Moro autonomy, the answer will need to be open to a great deal of political negotiation and undoubtedly requires participation from the local population. If the Bangsamoro people are ready for a change in Mindanao, then they are the players that can make that happen.

Edited by Helena Martin