Days in the Arctic: A Changed Way of Life

Big Business, Social Transitions, and Geopolitics in the Snow

"Village of Tasiilaq; View from Hotel Angmagsallik" by Christine Zenino. Licensed under CC BY 2.0

"Village of Tasiilaq; View from Hotel Angmagsallik" by Christine Zenino. Licensed under CC BY 2.0

My father and I took a long road trip through a remote part of Alaska a few years ago. After a long day, we pulled into a gas station to rest and buy a snack. Available food options were limited to a sandwich that consisted of only bread and mayonnaise that had passed its expiry date long before; the clerk told us there would not be another food delivery for weeks. Having lived in the far north my whole life, this experience was familiar. Even so, the question comes to mind: how long can this quiet, disconnected environment survive in the face of rapid development of the North? What do these changes mean for the daily life of someone living in the Arctic?

As sea ice melts and the Arctic heats up, major changes can be expected in the globe’s far north. The eight countries that make up the Arctic Council — Russia, Norway, Finland, Sweden, Denmark, Iceland, Canada, and the U.S. — each have their own plans to take advantage of the landscape. While they vary widely, some aspects, like population shifts, telecommunications infrastructure, and new shipping routes, are common themes. Twenty years from now, there will be more traffic, tourists, development and money than the Arctic has ever seen. The secluded gas station my father and I drove through is one of the many facets of northern life about to undergo a considerable transformation. It will impact the way Northerners interact with each other, find jobs, and participate in political processes. A glimpse of this future can be seen in Russia, Greenland, and Alaska.

In Russia’s north, where populations declined by up to 70 per cent when the Soviet Union collapsed, the demographics are once again changing significantly. For instance, Yamal, in central Russia, has seen its population increase by 20 000 foreign workers since the exploration of the world’s largest gas reserves, an initiative titled the ‘Yamal megaproject’. In the 1990s, Europeans constituted 80 per cent of Russia’s Arctic with population numbers consistently dwindling. However, thanks to increased oil and gas production, remote areas of northern Russia are seeing a population boom, courtesy of immigrants from Central Asia and China, making Russia the world’s second largest recipient of immigrants. As a result of the large influx of people from diverse backgrounds, sociologist Marlene Laruelle writes that a drastically different “ethnic composition” is forming north of the Arctic Circle: not quite Russian, not quite Indigenous, and not quite Asian. The changes have been described as a demographic crisis, but also as a symbol of northern Russia’s development as a modern society. People who have lived in Russia’s Arctic their whole life may be witnessing their land inherit a new culture for the third time: a person born in Yamal in 1960 could have been a devoted Communist Party member in the 1970s, a rampant oil tycoon in the 2000s, and now a piece of a multi-ethnic northern melting pot.

Migration to Yamal may be permanent, but in other Arctic regions, the arrival of foreigners occurs on a temporary basis. In the last decade, Iceland’s tourism industry has exploded with a 39 per cent increase in international visitors in 2016 and major cruise lines, like Holland America and Princess, are initiating their northern expansion. Greenland, however, may be the most impacted. The Greenlandic economy currently relies heavily on commercial fishing, despite economists’ attempts to diversify, but the Department of Tourism believes the impending tourist boom will spark a large economic and social shift with significant implications for daily Greenlandic life.

One change, for instance, is that this economic shift could be powerful enough to lead Greenland towards full independence from Denmark. Indeed, 70 per cent of Greenlanders support independence, but their government still relies on the Danish for 52 per cent of its public expenditure. By employing more of those who are not absorbed by the fishing industry, the Greenlandic economy would be strengthened by providing locals a higher volume and wider scope of jobs. Infrastructure would also improve, thanks to the airports and hotels needed for the expansion. The implications of a tourism boom, however, are also cultural. With less reliance on commercial fishing, more attention can be diverted towards protecting Inuit fishing traditions, which have been in a long struggle against organizations like People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals whose anti-sealing campaigns “are devastating for [Inuit] communities.” Local artists would also benefit from international visitors providing a new market for goods like soapstone carvings. A tourism boom could bolster Greenland, both economically and culturally, to a point where they can declare national independence, a title they have been longing for since the 1970s.

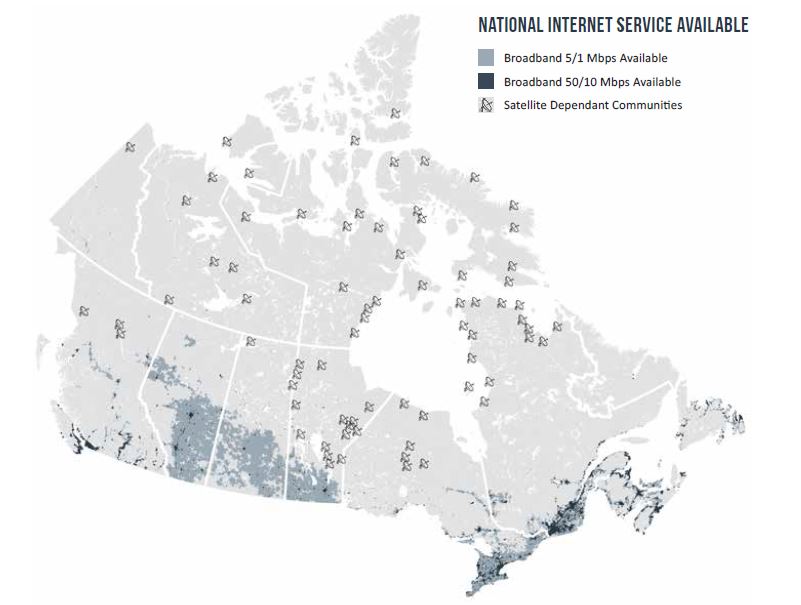

Despite these developments, a few key differences between the far north and their mother countries remain. For example, imagining life without the Internet is nearly impossible in Ottawa, yet the Internet is just reaching many in Nunavut. Even though there are small pockets with cellphone service, the majority of rural areas are in a “blackout zone,” but communication infrastructure is developing quickly. Finnish and Canadian governments have pledged to provide Internet across the Arctic, with the Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission (CRTC) declaring it a “basic human right” in 2016. The Canadian federal government subsequently invested $500 million into rural internet. In 2017, nearly 2000 kilometres of previously unserviced Alaskan coastline was delivered fibre-optic cable, with similar expansions announced in Norway and Russia that year.

The rapid northern proliferation of the internet highlights how quickly the Arctic can change. Nunavut government officials admitted that, in 2017, it was more efficient to send a thumb-drive by mail than use the Internet to transport information. However, Bell announced in 2019 that “high-speed internet and LTE wireless service are now available in all 25 Nunavut communities.” When it arrives, reliable, cheap, and fast connection to the internet will drastically change northern communities, making everything from small business operation to personal communication more efficient.

These transitions demonstrate that developments in the Arctic are varied and will impact many facets of northern life and that it is not only the climate that is changing. The quiet isolation of the Arctic is disappearing, leaving in its place social progressions and new economic opportunities. Distinct cultural identities, political independence, and cell phone towers will be the new reality. The next time my father and I visit that Alaskan gas station, it is possible we will drink Starbucks coffee and watch a cruise ship pass by.

Featured image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons. “Village of Tasiilaq; View from Hotel Angmagsallik” by Christine Zenino is licensed under CC BY 2.0

Edited by Sara Parker