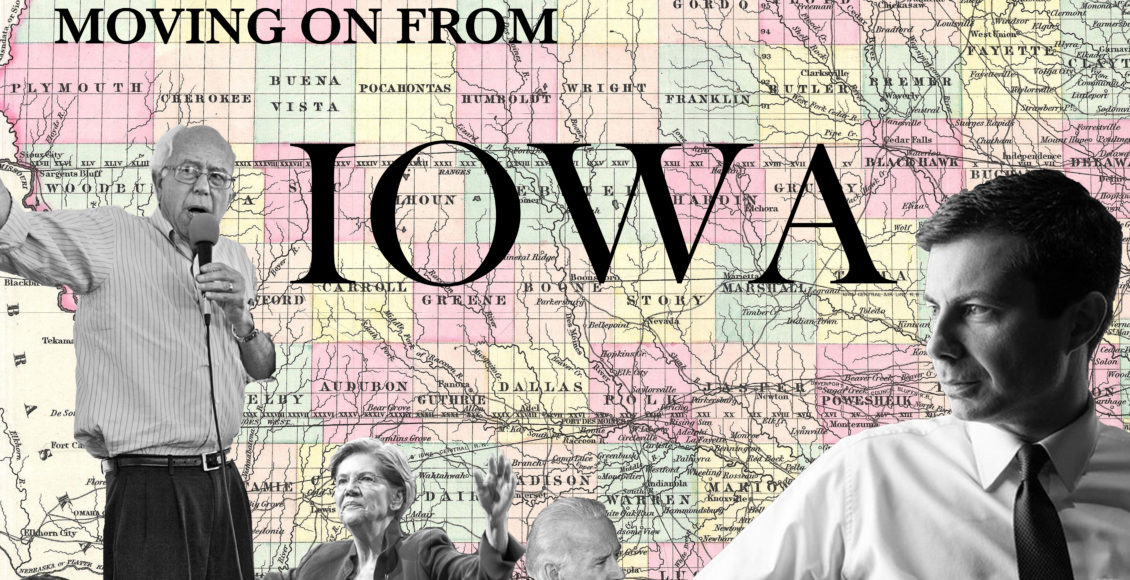

Moving On from Iowa

The Iowa caucuses are the first phase of the American Democratic primaries. After a unique caucusing process, numbers of “state delegate equivalents” are allocated to each candidate based on their share of the vote. These numbers will determine the number of delegates that will vote for each candidate at the Democratic National Convention in July. However, the 2020 caucuses have been complicated by errors in reporting the results, leading to uncertainty about who really won the caucuses, and doing nothing to clarify the potential future of this fraught race.

The Iowa caucuses, an unusual political process, have been a central part of the Democratic race for president since the 1970s, when campaigns began to develop a strategy founded on winning first in Iowa. In the 1980s, when party leaders pushed for official status as the first state in the country, with New Hampshire coming second, Iowa’s role was secured. The state has played an integral role in campaign strategy ever since; notably, Barack Obama’s win in the state in 2008 is often seen as his campaign’s first major breakthrough, setting him on the path to victory. His win over Hillary Clinton reshaped the race and demonstrated his electability to voters in the later states. Historically, over half of Iowa caucus winners have gone on to win their party’s nomination, which is confirmed and announced at the Democratic National Convention in July, after every state has voted.

Barack Obama campaigns in Iowa in 2007. Obama went on to win the state, the Democratic nomination, and the presidency. “Barack Obama in Onawa” by IowaPolitics.com is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0.

While Iowa is, in theory, only a minor player in the Convention, with its small population guaranteeing it far fewer delegates than players like California or Texas, its role as first in the process has made it instrumental for candidates to prove that they will perform well in later states. Furthermore, Iowa’s results tend to shape both public opinion and media coverage of the ongoing primary process. In the 2020 race, it was anticipated that Iowa would help determine a clear frontrunner out of the four top-tier candidates—Joe Biden, Bernie Sanders, Elizabeth Warren, and Pete Buttigieg—and narrow the crowded field, shaping a clearer path forward to the general election. But, as the past week has shown, the caucuses have arguably had the opposite result.

The 2020 caucus process was already going to be an unprecedented one: for the first time, the Iowa Democratic Party would be reporting three sets of data. Usually, caucuses only had to report state delegate equivalent data back to the state party, revealing how many delegates each candidate would receive based on their vote count. This year, the party released the first and second alignment numbers as well, which represent the vote counts before and after the elimination of candidates who did not meet a minimum level of 15% support. While winners were still to be determined by state delegate equivalents, the additional data was intended to provide more room for analysis of the outcome, and could potentially paint multiple candidates as winners.

After the change in data reporting and the anticipation of having more information about the Iowa caucuses, there was ultimately a huge delay in reporting results on the actual data. When the delay in reporting was revealed on the night of February 3rd, state party officials released a statement associating the confusion with the three sets of data, citing “inconsistencies” in their reporting. Entering the data had taken “longer than expected,” according to Iowa Democratic Party (IDP) Chairman Troy Price. The cause of this delay and of the inconsistencies in vote counts was unclear to the IDP, so they launched an investigation, eventually finding the root of the problem: an application the party had commissioned to speed up the reporting of results. The application was developed by Shadow Inc., a company known for making campaign software for Democrats, and was used by volunteers in the precincts to record and submit all three sets of data to party authorities. However, unbeknownst to the public, problems began to surface before voting began, when volunteers had difficulty downloading the application at the last minute, revealing that they had not received any training on how to use the software. Only a quarter of the nearly 1700 districts managed to successfully download and use the application.

Furthermore, the IDP found a “coding issue” that led to only partial data being reported from the caucuses even once the app was working. The IDP had thought of a backup plan, which would allow for volunteers to manually call-in results to the headquarters, but there were not enough staffers in place to report the data by phone, which led to hours of delay even after the issue had been identified. Although the IDP had been advised by the Democratic National Committee (DNC) to commission an application rather than using phone-in reporting, they became overly reliant on the application, leaving less than adequate resources for the backup plan. Instead, volunteers had to recount votes from paper worksheets by hand, which took even longer than expected due to the three sets of data. The IDP released results gradually, reporting only 62% of precincts two days after the caucuses ended, and not reaching 100% until the night of February 6th.

Yet, once 100% of precincts had reported their results and the IDP had released them, a CNN analysis found errors in the data. Some counties reported a different number of state delegate equivalents than the IDP had assigned them. In some precincts, the final vote exceeded the original vote, even though no new caucus-goers were permitted to enter the room and in fact, some were permitted to leave before the final vote. These inconsistencies do not appear to have any bias in favour of one candidate, but they make it impossible to fairly declare a winner, particularly in what turned out to be an extremely tight race between the top two contenders. With 100% of precinct results reported, Pete Buttigieg received 26.2% of state delegate equivalents, while Bernie Sanders received 26.1%. Consequently, Buttigieg has been assigned 13 delegates, and Sanders 12. Of Iowa’s 41 delegates, 8 went to Elizabeth Warren, 6 to Joe Biden, and 1 to Amy Klobuchar, so one delegate remains that has not been allocated. The reason for this remains unclear, but it is likely due to the close margin between the top two candidates, leaving open the possibility for a tie in delegate counts. The Associated Press, which announced the delegate tally, determined that they are unable to declare a winner. The Sanders and Buttigieg campaigns, however, both declared victory.

Bernie Sanders with supporters in Iowa in July 2019. Sanders is one of two candidates to declare victory following the release of Monday’s Iowa results. “Bernie Sanders” by Gage Skidmore is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0.

Despite the uncertainty, the candidates have already left Iowa behind, turning to Tuesday’s New Hampshire primary. Both disputed Iowa winners have high stakes in New Hampshire. Sanders is counting on a decisive victory in the state to help rally the left wing of the Democratic Party and finally push ahead of Joe Biden in national polls. Conversely, if Buttigieg is unable to win New Hampshire, his campaign, which lacks support among voters of colour and urban voters in the upcoming states, is likely to falter. The two candidates are currently tied, once again, in the New Hampshire polls, and were pointedly targeted by their fellow candidates in Friday’s debate. Ultimately, the Iowa caucuses failed to narrow the field and produce a new frontrunner, placing an even greater burden on New Hampshire.

Pete Buttigieg at a campaign rally the night before the Iowa caucuses. He holds a very narrow lead over Sanders in the reported results of the caucuses. “Pete Buttigieg Rally at Lincoln High School” by Phil Roeder is licensed under CC BY 2.0.

While it may never be known for sure who won or what exactly happened in Iowa, and the chaos will hopefully be a one-time occurrence. Officials in other states, like Nevada, have begun considering alternatives to application-based reporting. However, it is too late for early states, such as New Hampshire, to apply the lessons learned in Iowa, so there may be a few more messy primaries in 2020. Even more change may be afoot as critics, including former DNC chairman Howard Dean, have called for an end to Iowa’s “first in the nation” status and denounced the caucus process as unfair and overly complicated. The process has drawn criticism for years, partly because of its complicated nature, but attention is also paid to Iowa’s lack of diversity, which gives a disproportionate amount of political influence to a state that is not representative of the country. Caucuses themselves have been described as outdated, time-consuming, and inaccessible for many voters, and there have been calls for Iowa to hold normal elections like the majority of states. It’s possible that this incident will be the final straw leading to the end of Iowa’s importance in the primary process, only the first of many changes that might occur as a result of the, now officially in progress, 2020 election.

Feature image created by Charlotte Reed.