New Caledonia: Fighting for Independence in 2020

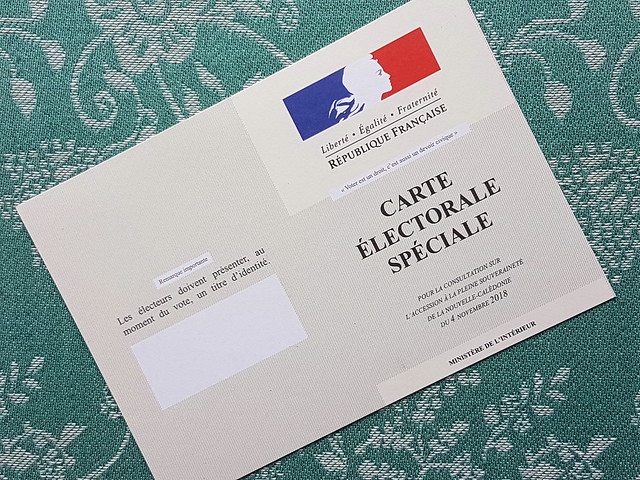

On October 4 of this year, New Caledonia rejected independence from France for the second time in two years, with 53.26 per cent of voters answering “No” to the question: “Do you want New Caledonia to attain full sovereignty and become independent?” After 167 years of French dependency, the referendum’s close results suggest deep social and political divisions within the Pacific archipelago.

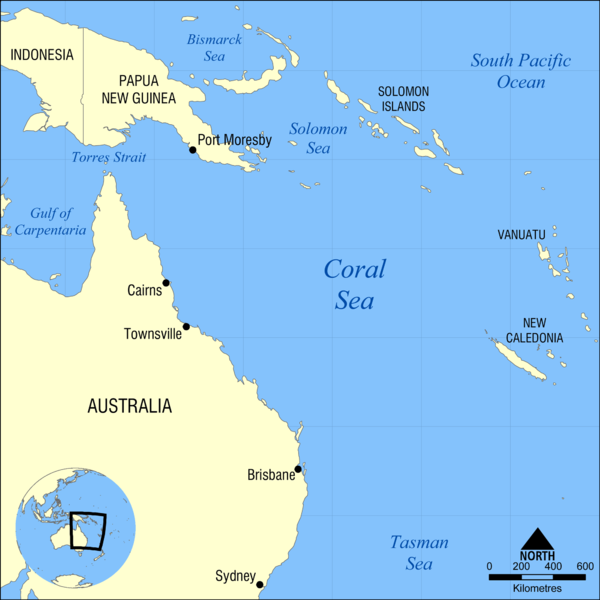

New Caledonia is situated in the southwest Pacific Ocean, 1200 km east of Australia. The archipelago became part of the French colonial empire in 1853, initially serving as a penal colony and then as a source of nickel for the metropole. The islands became an overseas territory in 1946 following World War II, granting French citizenship to all New Caledonians. Violent independence conflicts emerged in the 1980s between the Kanaks, the Indigenous inhabitants of New Caledonia, and the Caldoches, the European settlers living in New Caledonia.

The fight for independence in New Caledonia has been ongoing since the 1970s. Between 1976 and 1988, growing pro-independence sentiment emerged among Kanaks, facing fierce opposition from the European population. This “Kanak awakening” is attributed to a new generation of Caledonian students returning from France after experiencing the student uprising in May 1968, coupled with French “recolonization” of New Caledonia, spurred by a nickel boom in the same period.

Bloody confrontations between Kanaks and Caldoches increased in the 1980s, prompting the French government to deploy 6000 peacekeeping gendarmes in 1984. Two years later, the United Nations added New Caledonia to the “Special Committee on Decolonization,” where it remains to this day, fuelling Kanak’s support for independence despite continued racial tensions. The Kanak struggle culminated in April 1988, in a hostage-taking situation pursued by Kanak liberationists in Ouvéa who killed 19 Kanaks and two French, worsening the relationship between Kanaks and Caldoches.

These conflicts occurred against the backdrop of broader political mobilization. The Kanak and Socialist National Liberation Front (FLNKS), a pro-independence coalition of political parties, was founded in 1984 to represent all independence supporters, especially Kanaks. The Front’s organization is complex but includes many different left-wing parties, such as the Caledonian Union (UC), the National Union for Independence (UNI), and the Marxist inclined Party of Kanak Liberation (PALIKA).

Giving in to pressure from pro-independence activists, France introduced the first independence referendum in 1987, in which only 1.7 per cent of voters favoured independence. The result was severely lopsided because the FLNKS boycotted the vote, rejecting the referendum as a genuine act of self-determination. Indeed, it was evident that the French government favoured the anti-independence side, as French Prime Minister Jacques Chirac declared in 1986 that France would prefer that New Caledonia remain a French territory. Besides, the vote was not supervised by an international organization but by French judges and gendarmes. This first referendum’s outcome highlighted New Caledonia’s racial and political issues, along with the complicated prospect of achieving full sovereignty.

Moreover, the outcomes of New Caledonia’s referendums reflect the archipelago’s demographics. According to 2019 estimates, Kanaks represent approximately 40 per cent of the population whereas Caldoches are less than 30 per cent; the rest of the population consists of Wallisians and Futunians, Tahitians, Vietnamese, and others. Kanaks and Caldoches represent the independence and anti-independence causes, respectively, while the rest of the population has historically embraced the political interests of the Caldoches. Thus, New Caledonia finds itself in a situation where the largest ethnic group was and still is unable to control the political agenda.

Today, the FLNKS’ primary source of opposition comes from the Loyalists, who reject independence and wish to continue New Caledonia’s colonial relationship with France. Mainly supported by European settlers and their descendants, the Loyalists defend their Christian ideals and economic ties with France, with a coalition made up of six political parties, including the far-right National Rally.

To end conflicts between the two ethnic groups and increase the Kanaks’ political power, France signed the 1998 Nouméa Accord with New Caledonia, committing to three independence referendums in 2018, 2020, and 2022. Although a third referendum is scheduled, the approval of one-third of New Caledonia’s congress is needed to trigger the referendum in 2022, renewing the archipelago’s chance to attain full sovereignty.

This year’s close margin resulted from Kanaks’ large youth voter turnout, achieved through successful communication on social media. In contrast, the French mainstream media did not cover the referendum heavily, alienating many anti-independence voters. However, the situation surrounding the referendums is still tense, as Loyalists attempted to cancel votes from nine polling stations, claiming false intimidation from the FLNKS.

A successful third referendum in 2022 would mean the end of French aid to the overseas territory after a transition period. France currently pays New Caledonia an annual subsidy of 1.5 billion euros, representing 15 per cent of the archipelago’s GDP. The Loyalists argue that losing such an essential source of financial aid would damage New Caledonia’s economy, which is already highly dependent on tourism and the nickel trade.

Given the tense situation, France promised to remain neutral and not to interfere in Caledonian independence politics. President Emmanuel Macron has kept this promise since his election in 2017, welcoming the result of the second referendum as a “mark of confidence in the French government, with a profound sense of gratitude,” in a message broadcast the day of the referendum. The President also made a historic and symbolic visit to the archipelago in May 2018, marking the 30th anniversary of the Ouvéa cave hostage taking.

Arrivée en Nouvelle-Calédonie.

Au programme : Nouméa, Koné et Ouvéa – trois jours pour la mémoire et à la rencontre de ce qui fait la richesse de ce territoire. pic.twitter.com/qM61RKzKiG— Emmanuel Macron (@EmmanuelMacron) May 3, 2018

President Emmanuel Macron visits New Caledonia in 2018, commemorating the 30th anniversary of the Ouvéa cave hostage taking. Via Twitter.

France has a vast colonial legacy and a troubling history tainted by extensive corruption, dirty wars, and shady mercenary networks. To this day, France still holds about twelve overseas territories worldwide, making it the country with the most time zones and the largest exclusive economic zone. Long after the French colonial empire’s formal end, its territorial holdings continue to uphold France’s global power, influence, and economic prosperity.

Nevertheless, precedents do exist in French history for granting former colony independence via referendum. In 1977, after three referendums, vote-rigging, international pressure, and violent protests, France granted the territory of the Afars and the Issas its independence, prompting the formation of the Republic of Djibouti. Likewise, only 630 km north of New Caledonia, Vanuatu obtained its independence in 1980 in a similar way to Djibouti, following years of bloody protests.

Because independence conflicts are primarily associated with the decolonization period of the second half of the 20th century, seeing a territory demand full sovereignty in 2020 may seem unusual. Yet, New Caledonia exemplifies the complex and violent path towards independence, illustrating the reality of colonialism’s present-day impacts and consequences, even after 167 years.

Featured image: “Lagoons and Reefs of New Caledonia” by NASA Goddard Photo and Video is licensed under CC BY 2.0.

Edited by Luca Brown