Pandemic Economy: Recovery Expectations and Pivotal Opportunities

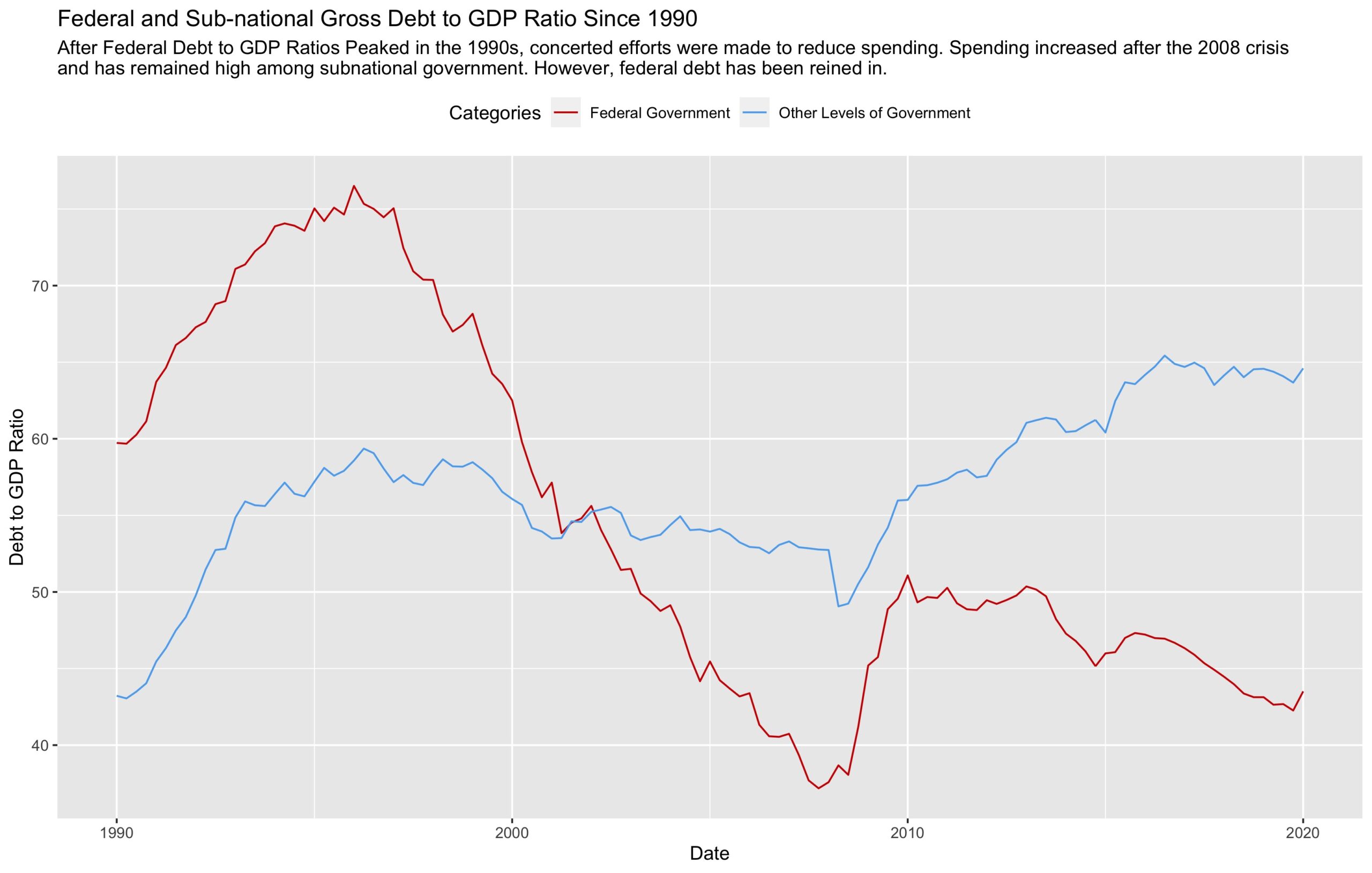

On July 8, an updated federal budget was released to the Canadian public, projecting the country’s deficit to break $1.2 trillion — a tenfold increase. While the spending has been necessary to protect working Canadians from the pandemic-induced recession, the route out remains murky. With personal debt and housing prices rising over the past decade and the oil and aviation sectors hard hit during the pandemic, it is difficult to see where funds to jumpstart the economy will come from. However, experts say that the federal government has the capacity to service this debt and even pay it off, potentially in the next ten years, so long as the recession lasts no more than a year.

Provinces have shouldered the majority of health related spending during the pandemic, amplifying their debt loads, which are already the largest in the country. Of course, the use of austerity measures to cut government spending and curb debt is a traditional method to tackle a large deficit. However, Doug Ford’s recent experience provides a cautionary tale: months ago his disapproval rating nearly reached 70 per cent due to austerity measures. However since the Ford government’s record COVID-19 spending, his popularity has soared. In Newfoundland and Labrador, spending cuts in recent years have also been criticised for hurting the province’s economy. More importantly, perhaps, cutting services related to health immediately after a pandemic would be painful should another wave of the virus arise. If the remaining stimulus cannot come from the government, then where will it come from?

Personal Spending and Houses: Crisis Attenuated by Pandemic

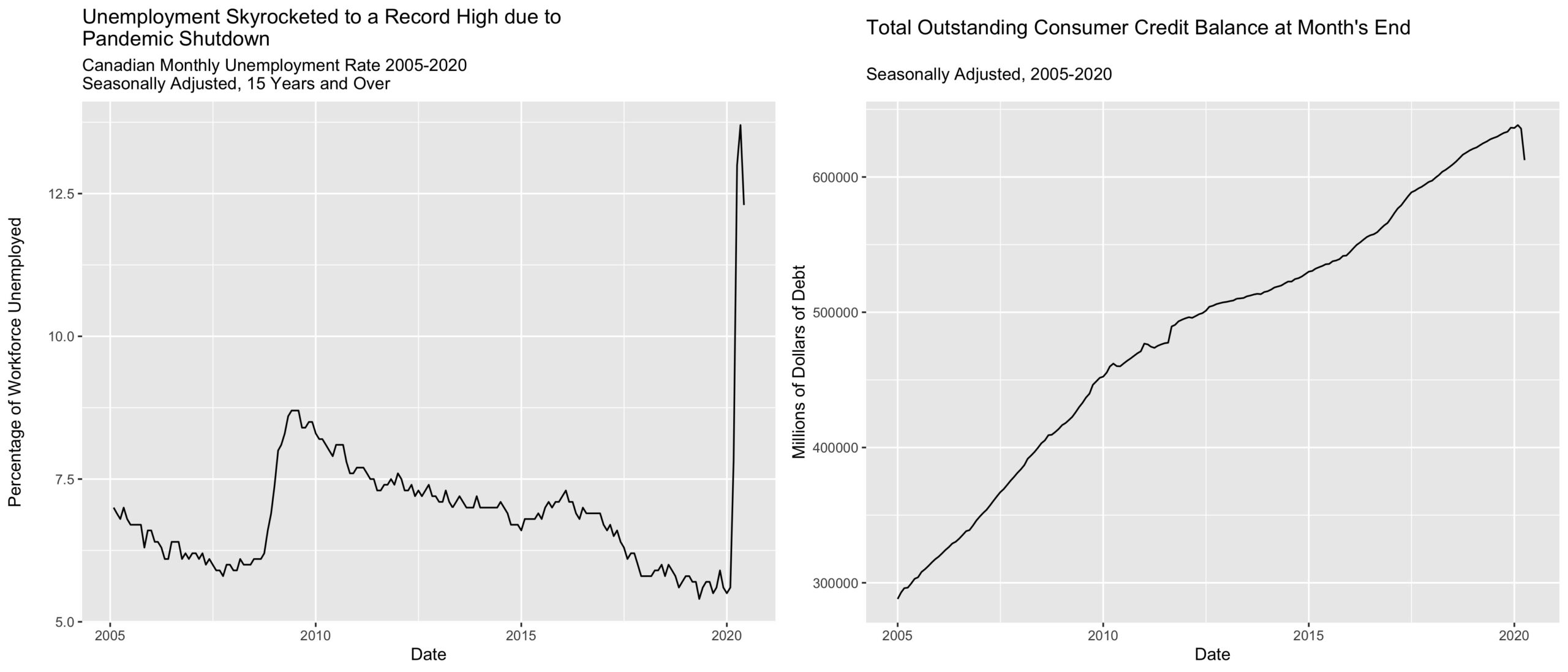

During fall 2019, rising employment was largely attributed to a combination of tech sector growth in Quebec, Ontario, and British Columbia alongside increases in part-time employment among youth. Part-time employment and jobs within the “gig economy” were the first to be lost during the pandemic, though. Companies quickly shed workers where they could, while sectors unable to provide online work to employees, such as retail, were faced with layoffs. In June, with the economy seemingly in rebound, unemployment fell to 12.3 per cent after close to a million jobs were added. While high unemployment explains the drop in consumer credit, anticipation of a rebound once the economy recovers may be ill-founded, as many Canadians may choose to pay off debt in the wake of a recession rather than increase their spending.

While increases in employment are positive, just two years ago, former governor of the Bank of Canada Stepehen Poloz wrote that ballooning consumer debt and housing prices were only sustainable because Canadians were seeing larger income increases. Since March, that is no longer the case. The Bank of Canada has since slashed the lending rate for commercial banks to 0.25% making it cheaper for Canadian businesses and individuals to borrow.

At the same time, while some may have expected Canada’s housing market to finally cool down, many suburbs are seeing prices stagnate or increase. In Calgary, although construction ceased for the first months of the pandemic, new construction is now increasing quickly. Across Ontario and Quebec, bidding wars have actually soared during May and June due to a low inventory of homes being sold. Overall, the housing market has remained similar to last year: markets in and around urban centers remain hot, while many outlying areas have depressed sales. In some cities, however, the pandemic has caused this trend to slow down so that detached homes in suburbs are becoming more popular for those who can afford them. In June, credit in the form of mortgages actually grew by 7.4 per cent.

Important Canadian Economic Sectors Flounder

In March, global crude prices fell as a result of Saudi Arabia and Russia’s price war, paired with falling demand due to the pandemic. Consequently, Canada’s oil sector, which relies on high prices to stay profitable, suffered greatly. Federal aid for the sector has yet to materialize, which can be attributed, in part, to fear of alienating Liberal party supporters who expected a “green” government. In July, however, the Senate Finance Committee received an internal report stating that Canada would remain reliant on oil and gas for employment for many years to come. It is hard to see how Trudeau will balance the demands of his environmental agenda against those of alienated Albertans.

Aerospace has also suffered from the pandemic. In 2018, the sector contributed $13.1 billion to the Canadian GDP. Almost half of Canada’s aerospace industry is located in Montreal, and, due to reduced demand for parts, many companies have laid off employees. Abroad, many governments have supported their airlines, while in Canada, they have been left to flounder, which may explain the rush to remove social distancing measures on flights. Montreal is home to the headquarters of the International Civil Aviation Organization and its commercial counterpart, the International Air Transport Association. It remains to be seen whether Canada’s reputation within these organizations will be damaged by the government’s failure to support the industry.

Both the oil and aviation sectors produce for export, which requires high demand from other countries. In particular, linkages to the American economy in the oil and automotive sector indicate that the Canadian economy will not rebound completely until demand resumes elsewhere. Even once the US economy reaches previous levels, questions remain over whether new north-south pipelines will be completed due to recent court decisions and presidential nominee Joe Biden’s opposition to using tar sands oil. At the outset of the fall in oil prices, Canadian inflation fell by roughly half. In response, the Bank of Canada, already operating at a low overnight rate, began buying back government bonds from banks (quantitative easing) to encourage them to loan more. It remains unclear what the long term effect will be, though some fear it could increase inflation uncontrollably.

As Canada’s economy starts to recover, what are the ongoing effects of #COVID19 on #businesses? Check out our new data from the Canadian Survey on Business Conditions: https://t.co/BFEPuJ6ip0 #CdnEcon pic.twitter.com/ULhRJedjW6

— Statistics Canada (@StatCan_eng) July 14, 2020

What is a Successful Economic Recovery?

In 2019, the World Economic Forum, in its annual assessment of the world’s economies, found most countries to be unprepared for the future. So it should come as no surprise that many are currently advocating for the COVID-19-spurred recession to serve as an opportunity to pivot toward more sustainable policies — both socially and environmentally. In 2019, the United Nations Environmental Programme released a report stating that in order to meet climate goals, emissions will need to drop 7.6 per cent per year over the next decade. According to some, the pandemic shutdown will allow the world to meet that goal in 2020.

However, total shutdowns are not needed to prevent climate catastrophe. In fact, meeting environmental goals would cost only two years of no-growth spread out across 30 years, implying that growth rates would fall by only a fraction of a percent each year. The crux of a greener recovery will be placing a cost on emissions: revenue-neutral carbon taxes incentivize switching to greener alternatives without hurting consumer spending. Short term goals need to focus first on people’s health and second on increasing employment, while maintaining awareness that this pandemic and recession will affect the poorest Canadians most.

As #COVID19 hits the fossil fuel industry, a new report shows that renewable energy is more cost-effective than ever – providing an opportunity to prioritize clean energy & bring the world closer to meeting the #ParisAgreement goals.#ClimateActionhttps://t.co/Ijoarg0R2J

— UN Environment Programme (@UNEP) June 30, 2020

At least some of the provincial and municipal spending currently exacerbating subnational debt could be diverted from excessive policing budgets. In Toronto, for instance, police services cost $1.1 billion, but this funding could be reapportioned to help public transit deal with a decline in passengers, or homeless shelters cope with the pandemic.

The most important goal, perhaps, is not higher rates of GDP growth, but greater life satisfaction. The economics of well-being — or happiness — have become buzzwords since the late 2010s, and the fact of the matter is that income per capita is only part of the story of individual happiness; social services and corruption all play larger roles in explaining variation across countries. According to a recent poll by Environics reported in Maclean’s, 52 per cent of Canadians believe protecting the environment is more important than protecting jobs. Although Canadians report high levels of life satisfaction, would it be higher if we were to focus less on growth and more on our environment?

The feature image, “Ottawa – ON – Bank of Canada” by Wladyslaw is licensed under CC SA 3.0.

Edited by Clariza-Isabel Castro