Xi Jinping: Drought and the 20th National Congress of the Chinese Communist Party

Overview of the Drought

The current drought in China is the worst the country has seen in recent history. For over 100 days, some cities have consistently reached temperatures as high as 45 degrees Celsius. The drought is affecting more than 900 million people and is likely the result of extreme climate change. As the country relies heavily on hydroelectricity, industrial cities, such as Shanghai and Jiangsu, have suffered under a stream of rolling blackouts. For instance, the Southwest province of Sichuan receives 80 per cent of its power from hydroelectricity (and also supplies approximately 30 per cent of China’s hydropower). This August, the province’s electricity production fell by half as Chinese businesses, factories, and households were forced to ration their power usage. This slump has also led to an increased reliance on coal, and the decreasing water levels of the Northern Yangtze river have strained China’s food production, compounding the damage.

Overall, the drought threatens China’s food security, water, and energy resources. As Xi Jinping continues to preach independence and economic self-reliance (especially after witnessing the continued sanctions on Russia), how will this affect his popularity in China, especially in the aftermath of the 20th National Congress?

What was the 20th National Congress?

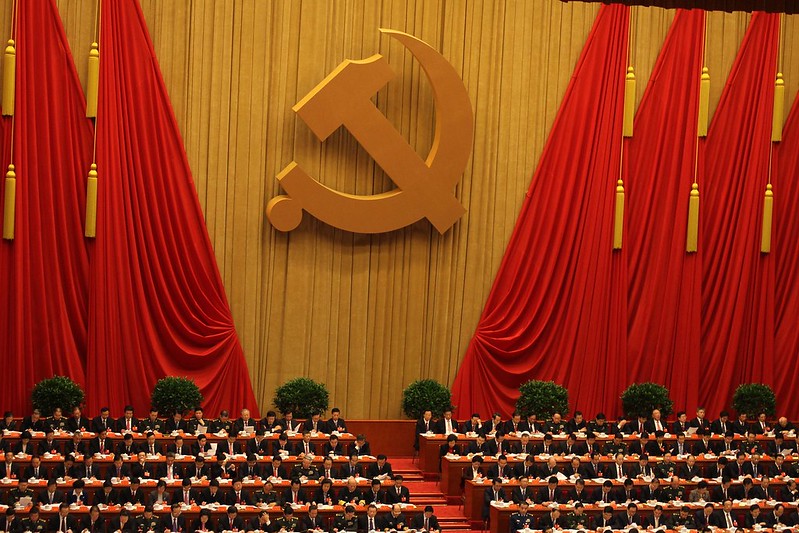

Held every five years in Tiananmen Square, the National Congress began on October 17, 2022. More than 2,000 members of the Chinese Communist Party body are elected as delegates and attend the weeklong meetings. Here, the 200 voting members of the Central Committee will select 25 individuals to become the Politburo (ministers and state leaders). Seven of those 25 individuals are then named as part of the elite Politburo Standing Committee (PSC), operating directly under Xi Jinping. Although most policy experts believe these roles are decided beforehand, the Congress presents itself as a unique opportunity for ambitious young members to get a glimpse into —and potentially join— the party’s ruling class.

Why does the 20th National Congress matter?

Xi faced numerous issues while seeking to consolidate his power at the Congress. The impact of his strict “zero covid” policy, extreme drought, deteriorating relations with the US, and the current economic impact of all of these factors posed significant problems for Xi. The 20th National Congress gives the world insight into the party leader’s vision for China during the upcoming years, as Xi aims to further consolidate power and popularity within the party. Teng Biao, a Chinese human rights lawyer, a argues that “[s]ince becoming the general secretary of the CCP 10 years ago, Xi has dramatically changed China’s political landscape.” Even the timing of this year’s Congress is telling. The date for the Congress is traditionally negotiated by the various political factions in the CCP and is usually held in November. These negotiations within the party’s elite are even more important when a leader is coming to the end of his second term. They signal which faction is aiming to make a bid to hold more power. The fact that this year’s Congress was held before November, in mid-October, signals the tight grip Xi hopes to keep on the CCP and its policy direction. Nick Marro from the Economist Intelligence Unit concludes that the continued “erosion of these internal checks-and-balances will worsen the risks and consequences of policy drift.” Xi Jinping’s anti-corruption campaign furthers this push for obedience, which has seen many of his rivals in government and businesses removed from their positions.

“Xi Jinping,” by Global Panorama, is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0.

Since being elected for an unprecedented third term in 2018, Xi has laid the groundwork for another win in the Congress. One of the many norms that govern the CCP is that only those aged 67 years or younger can be promoted; anyone older than 67 is considered to be of retiring age. This concept is known as qi-shang, ba-xia (literally: seven up, eight down) The acceptance of Xi’s age, as he currently stands at 69 years old, and the reinforcement of his power as the leader for a 3rd term demonstrates the shifting of norms that govern the CCP. Ahead of the Congress, the head of the Organization Department of the CPC Central Committee went so far as to claim that “the process of selecting representatives will become a process of in-depth study and implementation of Xi Jinping Thought on Socialism with Chinese Characteristics for a New Era.”

Bert Hofman at the National University of Singapore concluded no new changes emerged in terms of economic policies. Indeed, Xi Jinping’s appointment of Li Qiang as his new second-in-command demonstrates a clear preference for loyalty over expertise. Li Qiang’s predecessor, Li Keqiang, was seen as an experienced and moderate voice in a political landscape that was becoming aggressively conformist.

In further solidifying himself at the top of the leadership, he also risks bearing responsibility for failures in the eyes of the everyday Chinese citizen. This danger is most apparent in his “zero COVID” policy. Though the goal of zero COV remains unrealistic, he continues to implement harsh, even draconian, measures. Xi has said “[g]overnment, the military, society and schools, north, south, east and west — the party leads them all.” As he continues to position himself as the sole authority within the Party, China’s policy successes become his successes, and its failures, his failures.

Mandate of Heaven (Tianming)

“Drought causes Yangtze to shrink,” by the European Space Agency is licensed under CC BY-SA IGO 3.0.

The economic and environmental effects of the current drought cannot be overstated. While these are not the first rolling blackouts China has implemented, the prolonged drought combined with recent shutdowns of economic centres emerging from China’s “zero covid” policy has heavily impacted business and industrial areas across the country.

The drought’s overlap with the 20th National Congress brings forth an interesting parallel to a cultural phenomenon known as the “Mandate of Heaven.” While no longer widely held, the belief was common in the Chinese psyche for over 2000 years. Emerging from the ancient Zhou dynasty, it proposes that the ruler of a state had a divine right to rule but also a responsibility for moral leadership (wen). An immoral ruler was thought to be reflected by natural disasters (usually floods or droughts). In such instances, it was believed that people had the responsibility to rebel, protest or overthrow the ruler. With a drought occurring during the 20th Congress, what does this mean for Xi Jinping and his future political goals?

As the 20th National Congress lines up with severe drought, the parallels are clear: even with his effort to consolidate power, Xi’s Congress was a tense and precarious moment. The drought is forcing local governments to quell unrest emerging from a lack of water, extreme heat, and the closing of factories and industrial centres. The cementing of Xi’s popularity and unchallenged leadership is critical as the country struggles economically.

Featured image: “18th_National_Congress_of_the_Communist_Party_of_China,” by Prachai is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

Edited by Matthew Farrell